The year 2020 has brought us some wild and crazy things, including a novel virus that led to a global pandemic, a record-breaking number of hurricanes in the Atlantic, and, most recently, the discovery of previously unidentified salivary glands. The most astonishing to me is the discovery of the salivary glands; admittedly, I may be a little biased as all things dental-related pique my interest. How is it possible to have an organ that has gone undiscovered in a time that we have some of the best medical technology and advanced understanding of the human body?

New Tubarial Salivary Glands

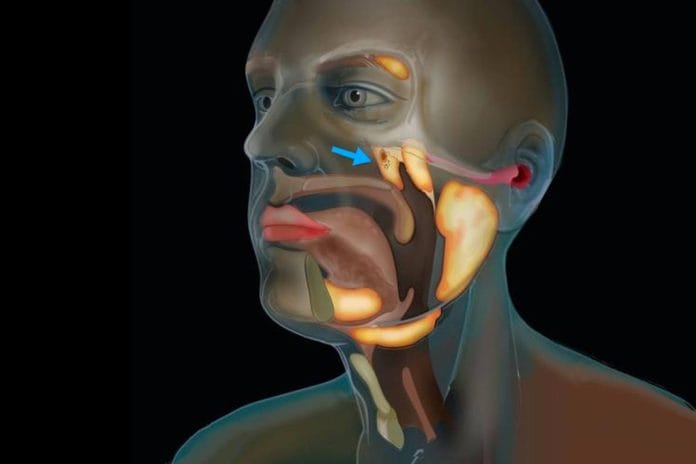

In an article published in the journal Radiotherapy and Oncology, the discovery is explained. (Valstar, et al. 2020). The discovery was made after a “visualization by positron emission topography/computed topography with prostate-specific membrane antigen ligands (PSMA).” 1 The salivary glands are sensitive to PSMA and exhibit high uptake, making them visible on scans.2 Though these salivary glands are touted as a “new” discovery when you look back at previous studies, you will see them described in the literature.

In a study published in 2018 aiming to “describe physiological PSMA-ligand uptake distribution characteristics in the head and neck,” the authors described seeing nasopharyngeal tracer concentration located around the area of the torus tubarius. This is the exact location described by the current study, which also lends to the name suggested for these salivary glands, tubarial salivary glands.2 This is not the only piece of literature published to describe these areas. In 2016 another study described the same tracer concentration around the fossa of Rosenmuller, an area anatomically located extremely close to the torus tubaris.3

I certainly do not want to steal the thunder of the authors of the current study, as they may not have been the first to “discover” the salivary glands; they are the first to actually look into the area and postulate the function of these salivary glands. The assumption of the physiological function is the “moistening and lubrication of the nasopharynx and oropharynx.” 1 This study confirmed the salivary gland’s presence in 100 men being treated for prostate cancer and two cadavers, one male and one female, using morphological and histological characteristics. The study provides a fantastic visual of the salivary glands in the article here.

Tubarial Salivary Glands Possibilities

The authors go on to describe their interpretation of the tubarial salivary glands; they layout three different possibilities. They describe these salivary glands as having the most similarities to the sublingual glands due to predominant mucous acini and the presence of multiple draining ducts. Taking this into consideration, the tubarial glands would qualify as a “fourth pair of major salivary glands.” 1

However, the tubarial glands also share many similarities with the palatal conglomerate of microscopic glands. This may lead to the classification of the tubarial glands as minor salivary glands. Another option mentioned by the authors is to classify all salivary glands together, making a “salivary gland system.” This would eliminate the need to classify salivary glands into major or minor categories and would not lead to the tubarial glands being a separate organ, but rather a macroscopic part of an organ system.1

The authors also explored the relevance as it applies to radiotherapy for head and neck cancer (HNC) by questioning if protecting the tubarial salivary glands could improve quality of life. Evidence shows high-dose external radiotherapy often used in the treatment of HNC as well as brain metastasis, causes toxicity in the salivary glands via interstitial fibrosis and/or acinar atrophy. This can lead to xerostomia and dysphagia, which both affect the patient’s quality of life. Though the authors encourage further studies to determine the relevance of the tubarial glands and quality of life following radiotherapy, they conclude, “Our findings indicate that sparing these tubarial glands could provide an opportunity to prevent side effects from radiotherapy and better maintain patients’ quality of life.”1

Other recent discoveries, such as the discovery of the body’s 79th organ, the mesentery that was identified by J. Calvin Coffey as recently as 2017, is further evidence that we have a lot to learn about the human body.4 Prior to the mesentery being added to Grays Anatomy as the 79th organ, it was thought not to have a real function. However, through the years, Dr. Coffey collected evidence and was able to confirm the mesentery performs an essential and/or vital function. Scientists are continuing their research on the mesentery and investigating its role in heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and high blood pressure, among other diseases. Additionally, there has been a connection between the gut, the mesentery, and the brain; further studies are needed to better understand this connection.

Tubarial Salivary Glands Conclusion

The discovery of these salivary glands should motivate all health care professionals to be aware of the many advancements that have contributed and will continue to contribute to our understanding of the body and its many amazing functions. I look forward to further studies to identify its role and function in the onset or prevention of disease, as well as future discoveries in the area of anatomy and biology of the human body. I sincerely hope we never quit learning new things and improving our knowledge and ability to understand the human body.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Valstar, M.H., de Bakker, B.S., Steenbakkers, R.J.H.M., de Jong, K.H., Smit, L.A., Klein Nulent, T.J.W., van Es, R.J.J., Hofland, I., de Keizer, B., Jasperse, B., Balm, A.J.M., van der Schaaf, A., Langendijk, J.A., Smeele, L.E., Vogel, W.V. The tubarial salivary glands: A potential new organ at risk for radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2020 Sep 23; S0167-8140(20): 30809-4. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.034. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32976871. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32976871/

- Klein Nulent, T.J.W., Valstar, M.H., de Keizer, B., Willems, S.M., Smit, L.A., Al-Mamgani, A., Smeele, L.E., van Es, R.J.J., de Bree, R., Vogel, W.V. Physiologic distribution of PSMA-ligand in salivary glands and seromucous glands of the head and neck on PET/CT. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018 May; 125(5): 478-486. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.01.011. Epub 2018 Jan 31. PMID: 29523427. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29523427/

- Demirci, E., Sahin, O.E., Ocak, M., Akovali, B., Nematyaza,r J., Kabasakal, L. Normal distribution pattern and physiological variants of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT imaging. Nucl Med Commun. 2016 Nov; 37(11): 1169-79. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000566. PMID: 27333090. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27333090/

- Coffey, J.C., O’Leary, D.P. The mesentery: structure, function, and role in disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Nov; 1(3): 238-247. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30026-7. Epub 2016 Oct 12. PMID: 28404096. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28404096/