Local anesthetic agents have been used in clinical dentistry to reduce or eliminate pain associated with invasive dental procedures since the early 19th century. Local anesthesia involves the injection of an anesthetic solution adjacent to the nerves that provide sensation to a region of the oral cavity where treatment will be delivered. Anesthetic solution temporarily prevents the propagation of nociceptive nerve impulses, allowing the pain-free delivery of dental treatment.1,2

Dental hygienists complete rigorous training in head and neck anatomy and the safe administration of local anesthesia, but alas, complications do arise.

Common systemic reactions due to local anesthesia are reported as psychogenic reactions, systemic toxicity, allergy, and methemoglobinemia. Local complications are reported as pain at the injection site, needle fracture, prolongation of anesthesia, various sensory disorders, lack of effect, trismus, infection, edema, hematoma, gingival lesions, soft tissue injury, and ophthalmologic complications.1

This article will focus on trismus, a bilateral restriction in mouth opening due to a tonic contraction of the muscles of mastication.3

Clinical Presentation of Trismus and Effected Population

The term trismus was used in the past to describe the effects of tetanus, also called “lockjaw.” Now, trismus is used to describe any restriction to the mouth opening, including restrictions caused by trauma, surgery, or radiation.3

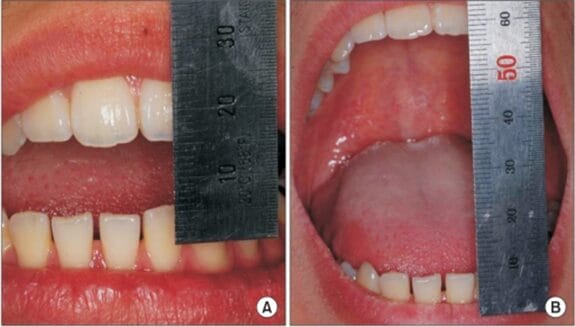

Normal mouth opening ranges between 40 and 60 mm or two to three finger breadths. Less than a 35 mm opening is considered a trismus case, but it varies for each individual (see Image 1).4 Limited jaw mobility can result from trauma, joint damage, scar tissue, or a combination of these factors.3

Image courtesy Kim, S.M., et al.5

(CC BY-NC 3.0 DEED)

Trismus is most likely to develop in:6

- Young adults aged 18 to 25 years old secondary to an associated pericoronitis with an impacted wisdom tooth

- Patients with head and neck cancer who received radiation (radiation-associated fibrosis)

- Patients with a temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD)

With TMD, trismus is classified as a myospasm or tonic contraction myalgia.6 Trismus can affect a patient’s quality of life and, in the long term, may lead to serious health implications. Trismus may interfere with everyday activities such as speaking, eating, and swallowing, complicating oral hygiene and the delivery of dental procedures.4

Trismus Related to the Administration of Local Anesthesia

Trismus related to the administration of local anesthesia is caused by several factors:1

- Multiple injections in a short time in the same area

- Intramuscular injection inside the muscle or trauma to the muscles, causing hematoma formation and fibrosis

- Needle fracture in the muscles inserting into the styloid process

- Inaccurate positioning of the needle when giving the inferior alveolar nerve block or maxillary posterior injection or inflammation of the masseter and other masticatory muscles

- A low-grade infection

- Excessive volumes of local anesthetic solution deposited into a bounded region causing, expansion of tissues

When an inferior alveolar nerve block or maxillary posterior injection is administered, it involves accessing the infratemporal fossa, which is an anatomical region with specific boundaries. The maxilla and zygomatic buttress define the front. The mandibular condyle and articular tubercle of the temporal bone define the back. The temporal bone and greater wing of the sphenoid define the inner side. The mandible’s ramus defines the outer side.7

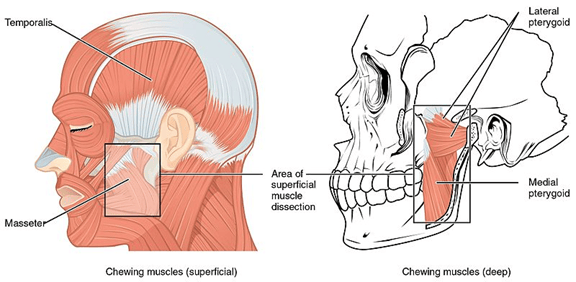

The infratemporal fossa is open at the bottom and extends along the mandibular ramus’s front edge to the alveolar ridge. Internally, it connects with the orbit through the pterygomaxillary and inferior orbital fissures. The temporalis, lateral and medial pterygoid muscles, inferior alveolar nerve, lingual nerve, maxillary nerves, internal maxillary artery, and its branches, as well as the pterygoid plexus of veins, are all located within this space (see Image 2).7

Image courtesy OpenStax

(CC BY 4.0 DEED via Wikimedia Commons)

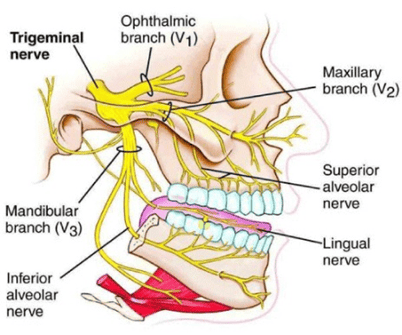

The inferior alveolar nerve stems from the posterior trunk of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (see Image 3). It runs deep to the lateral pterygoid muscle, descending into the pterygomandibular space, and enters the mandibular foramen.2

Image courtesy Al-Rawee, R.Y., et al.8

(CC BY 4.0 DEED)

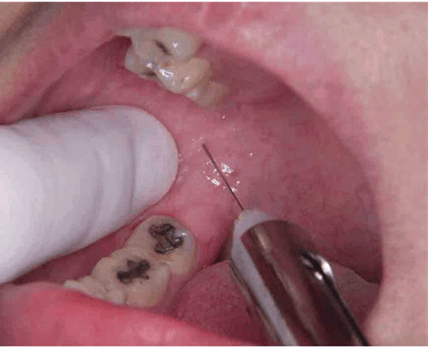

When administering an inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB), the dental syringe is positioned above the contralateral premolars, and a long needle is inserted 1 to 1.5 cm superior to the mandibular occlusal plane into the pterygomandibular depression to reach the pterygomandibular space. The pterygomandibular depression is located between the pterygomandibular raphe and the coronoid notch of the mandibular ramus. The coronoid notch is the most concave point on the anterior ramus, and it can be palpated with the non-dominant hand before the injection (see Image 4).2

Understanding the relationship of these structures to the inferior alveolar, maxillary, and mandibular nerves is crucial to decrease the risk of trismus from the administration of local anesthesia for dental procedures.7

Image courtesy Kriangcherdsak, Y., et al.9

(CC BY-NC 3.0 DEED)

Trismus is a complication of these injections because the masticatory muscles, mainly the medial pterygoid muscle, can be accidentally penetrated, resulting in pain-related trismus. When the affected muscle stretches, it triggers pain, causing an immediate reflex contraction and mandibular opening limitation. Trismus may also result from an intramuscular hematoma injury to the inferior alveolar artery or vein, leading to hematoma in the pterygomandibular space.2,4

When any muscle is damaged, a pain reflex may be stimulated, resulting in the muscle fibers engendering pain when they are stretched. This pain causes muscle contraction, resulting in a loss of range of motion. This contraction is a true reflex and cannot be controlled by the patient.3

Signs and Treatment

Signs of trismus are limited mouth-opening ability, deviation of the jaw toward the affected side, diffuse facial swelling (and fever if associated with an infection), and severe pain in acute cases. Symptoms include pain at rest, discomfort when yawning, difficulty with routine daily oral care, pain in one or more masticatory muscles, sensation of muscle tightness, cramping or stiffness, difficulty with speech, and inability to bite or chew on solid foods.6

Trismus due to local anesthesia administration is rare and generally resolves in less than two weeks, but permanent trismus can occur.1 Regardless of the immediate cause, immobilized joints quickly begin to show degenerative changes, including thickening synovial fluid and cartilage thinning. Studies have shown that muscles that fail to move through their range of motion for as little as three days begin to show signs of atrophy.3

Progression of trismus to chronic hypomobility and fibrous ankylosis may be prevented by the early institution of treatment in the acute phase consisting of heat therapy with a warm, moist towel for 15 to 20 minutes per hour, anti-inflammatory drugs, prescription of analgesics, soft diet, antibiotics (if infection is present), muscle relaxant such as diazepam 2.5 to 5 mg three times per day, or physiotherapy.1,4

Stretching exercises may be indicated after the acute phase, particularly when trismus persists for longer than one week. Exercises involve repeated attempts to open the mouth against applied resistance, usually divided into multiple daily sessions. Physical therapy alleviates edema and fibrosis, restores blood circulation, improves range of motion and muscle strength, and keeps the muscles active. Physiotherapy includes opening and closing the mouth and lateral movements for five minutes every three to four hours.4

Referral to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon may be considered if there is no improvement or in extreme cases of trismus.4

In Closing

Although rare, trismus can result from routine local anesthesia administration. Through continued education, dental hygienists should regularly refresh their knowledge of head and neck anatomy and local anesthesia administration skills.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Keskin Yalcin, B. (2020). Complications Associated with Local Anesthesia in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. In V. M. Whizar-Lugo & E. Hernandez-Cortez (Eds.), Topics in Local Anesthetics (pp. 151-164). Intechopen. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/67979

- Mathison, M., Pepper, T. (2023, June 1). Local Anesthesia Techniques In Dentistry and Oral Surgery. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580480/

- Trismus. (n.d.). The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/complications/trismus/

- Santiago-Rosado, L.M., Lewison, C.S. (2022, October 27). Trismus. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493203/

- Kim, S.M., Lee, J.H., Kim, H.J., Huh, J.H. Mouth Opening Limitation Caused by Coronoid Hyperplasia: A Report of Four Cases. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014; 40(6): 301-307. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4279969/

- Auluck, A. How Do I Manage a Patient with Trismus? J Can Dent Assoc. 2016; 82: g8. https://jcda.ca/g8

- Afradh, M., Shenoy, J.V., Kumar, S., et al. Comprehensive Review on Complications of Local Anesthesia in Oral Procedures: Focus on Trismus. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews. 2024; 5(1): 539-541. https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V5ISSUE1/IJRPR21587.pdf

- Al-Rawee, R.Y., Abdalfattah, M.M. Anatomy Respect in Implant Dentistry. Assortment, Location, Clinical Importance (Review Article). J Dent Probl Solut. 2020; 7(2): 68-78. https://www.peertechzpublications.org/articles/JDPS-7-188.pdf

- Kriangcherdsak, Y., Raucharernporn, S., Chaiyasamut, T., Wongsirichat, N. Success Rates of the First Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block Administered by Dental Practitioners. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2016; 16(2): 111-116. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5564079/