After successfully completing dental hygiene school, we often think we know all there is to know about the anatomy of the head and neck. Dental hygiene students dive deep into the details of head and neck anatomy; however, the body is complex, and our education only goes as far as what is documented in the literature. In October 2020, a study identifying a new salivary gland was published, highlighting the cliché, “We don’t know what we don’t know.”6

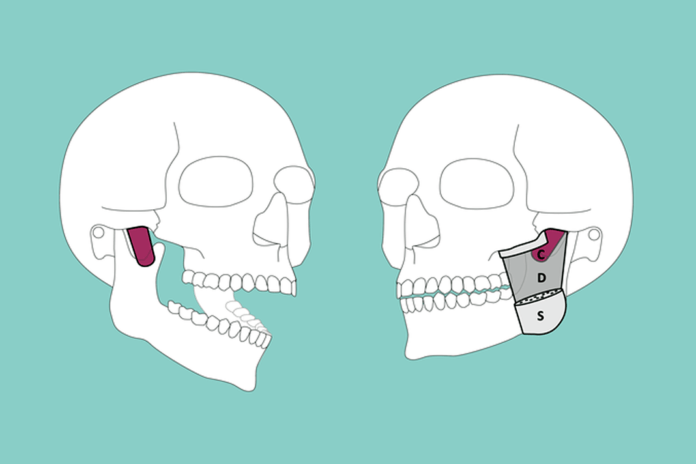

In December 2021, a study identifying yet another anatomical feature of the head and neck was published. This new feature is part of the masseter muscle. In the past, the masseter muscle has been described with two layers, the superficial masseter muscle, and the deep masseter muscle. This recent discovery identifies a third layer identified as the deepest layer, which originates “posteriorly on the inner, temporal side of the zygomatic process of the temporal bone, with the muscle fibers running diagonally anteriorly, the muscle attaching at the base and along the posterior margin of the coronoid process of the mandible.” The authors suggest the Latin name M. masseter, pars coronoidea; however, they refer to it as the “coronoid part” of the masseter muscle currently.1

This isn’t the first time a three-layer masseter has been described. In 1784, von Haller postulated that the masseter “may consist of two or three layers.”1,2 In the 38th edition of Gray’s Anatomy (1995), the muscle was described as consisting of “a superficial, a middle and a deep layer.”1,3

More recent literature also describes the masseter muscle as consisting of three layers. In 2000, an article was published in the journal Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy that describes the masseter muscle as seemingly consisting of three layers, “overlapping from front backwards like the tiles of a roof.”4 In a study published in 2003, the authors describe the masseter muscle as “a typical penniform structure, and that it is divided into three anatomically and functionally distinct parts.”5

Coronoid Part of Masseter Muscle

The origin of the coronoid part of the masseter muscle is described as posterior to the temporomandibular joint. Muscle fiber orientation runs parallel and diagonally, and they are elongated and quadrangular with an average anterior length of 22.8mm, posterior length of 20.7mm, anterior width of 9.2mm, posterior width of 12.7mm, and thickness of 2.0mm.1

The main innervation of the coronoid part is a branch of the masseteric nerve. The mandibular nerve is described as passing “through the gap between the posterior border of the coronoid part and the condylar process.” Mezey et al. postulate a possible source of innervation from the inferior alveolar nerve and, alternatively, the long buccal nerve. Blood supply is suggested to come from the maxillary artery.1

The authors describe the function of the coronoid part as “stabilizing and retracting the anterior-superior part of the mandible.” The authors suggest further studies to support and confirm their anatomical findings and provide a more detailed analysis of the functions of the coronoid part of the masseter.1

The importance of this discovery in treatment for temporomandibular disorder as well as other orofacial pain cannot be dismissed. Though the significance of the function of the coronoid part of the masseter muscle needs further studies, the authors are confident it is a functional part of the complex muscles of mastication.

As clinicians, staying abreast of new developing discoveries and their role in providing comprehensive care to patients is imperative. Though we often assume our understanding of anatomy and physiology is complete upon graduation from dental hygiene school, the past two years have provided discoveries (tubarial salivary glands6 and coronoid part of the masseter muscle) of anatomical features that were likely not discussed or studied in the past.

All clinicians should be encouraged to remain diligent in their continuing education as we learn more regarding the function of the “coronoid part” of the masseter.

Need CE? Check Out the Self-Study CE Courses from Today’s RDH!

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Mezey, S.E., Müller-Gerbl, M., Toranelli, M., Türp, J.C. The Human Masseter Muscle Revisited: First Description of Its Coronoid Part [published online ahead of print, 2021 Dec 2]. Ann Anat. 2021; 240: 151879. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2021.151879. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0940960221002053?via%3Dihub#bib5

- Haller, A.v., Soemmerring, S.T.v., Wrisberg, H.A., Meckel, P.F.T. (1788). Grundriss der Physiologie für Vorlesungen. Germany: Haud und Spener.

- Williams, P.L. (Ed.), Gray’s Anatomy (38th ed.), Churchill Livingstone, New York (1995).

- Gaudy, J.F., Zouaoui, A., Bravetti, P., et al. Functional Organization of the Human Masseter Muscle. Surg Radiol Anat. 2000; 22(3-4): 181-90. doi: 10.1007/s00276-000-0181-5. PMID: 11143311. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11143311/

- Brunel, G., El-Haddioui, A., Bravetti, P., et al. General Organization of the Human Intra-masseteric Aponeuroses: Changes with Ageing. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003; 25(3-4): 270-283. doi:10.1007/s00276-003-0125-y. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13680179/

- Valstar, M.H., de Bakker, B.S., Steenbakkers, R.J.H.M., et al. The Tubarial Salivary Glands: A Potential New Organ at Risk for Radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2021; 154: 292-298. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2020.09.034. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32976871/