When I was younger, I would go to the library, find an encyclopedia, and look up the answer if I had a question about something. Today, I have information at my fingertips, which has turned out to be a gift and a curse. It’s a gift because I can access this information from anywhere. However, it’s a curse because it is information overload, and determining what is real and what is fake has become increasingly difficult.

Information overload has become so problematic that it now has an official title, “infodemic.” Infodemic is described as “the rapid spread of information – both accurate and inaccurate – in the age of the internet and social media.”1 Though many may assume this term originated during the pandemic, in fact, it was coined in 2003.1

Though the infodemic was clearly problematic during the pandemic, the concern was established long before COVID-19 hit the search bar. Many may think that an infodemic isn’t a huge concern. On the contrary, the infodemic has contributed to confusion and risk-taking behaviors that can harm health. It has also led to mistrust in health care professionals, undermining public health responses and efforts.2

The best way to fight the infodemic is to arm yourself with the knowledge necessary to differentiate between robust evidence from misinformation and/or disinformation. Robust evidence is strong, reliable, and not easily refuted. It is evidence that’s supported by multiple studies and can withstand critical scrutiny.

Alternatively, misinformation is false or inaccurate information intended to deceive people, while disinformation is false information intended to mislead people. The spread of misinformation is generally unintentional. The person sharing the information may not realize it is misinformation. On the other hand, the spread of disinformation is intentional and is often intended to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.

Everyone is susceptible to misinformation and disinformation. Here are eight tips on how to vet a source to determine if the information is robust or potentially misinformation or disinformation. This is not foolproof. You will still need to use your critical thinking skills, but it is a good start to finding accurate information.

1) Is it current?

The first thing to address is that science is not static, especially medical or biological sciences. This doesn’t mean that it isn’t reliable. Science changes because we have learned more or have better technology to conduct testing and research. As a result, it is imperative to ensure the information you are reading is current. The rule of thumb is that it should have been published within the last five years.3

I must add one caveat: When there is an overwhelming scientific consensus, continuing to invest in research doesn’t make sense. Accordingly, the most current research may be over five years old, depending on the topic. For example, no current studies are testing the theory of gravity because it is well-established that gravity does, indeed, exist.

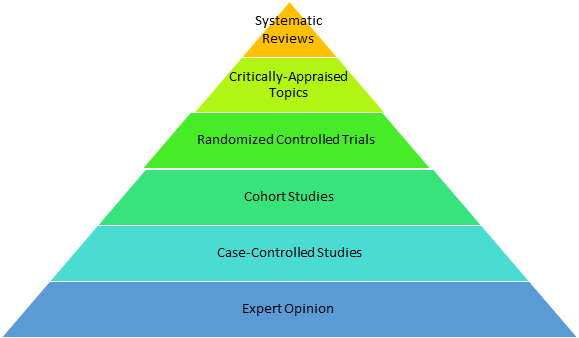

2) Mind the hierarchy of evidence

Next, we want to ensure we understand the hierarchy of evidence. The hierarchy of evidence is a core principle in evidence-based patient care. It helps clinicians identify the best evidence by categorizing studies based on the rigor (strength and precision) of the methods.4

Interestingly, there is a newer study design that is often omitted from the traditional hierarchy of evidence: Mendelian randomization analysis. Mendelian randomization is a study design that uses genetic variations to investigate causal relationships between potentially modifiable risk factors and health outcomes.5

It is often utilized in studies that would be unethical otherwise. For instance, a study that would require withholding treatment of a disease to determine causality could utilize the Mendelian randomization method to eliminate that ethical concern.5

Mendelian randomized analysis would fall between cohort studies and randomized controlled trials. Essentially, they are better than a cohort study but not as good as a randomized controlled trial. Nonetheless, the results from Mendelian randomized analysis generally infer causality.6

A quick search of the PubMed database yielded over 50 Mendelian randomized analyses on periodontitis. This means there is evidence to infer or eliminate causality between periodontitis and multiple chronic diseases and risk factors. Mendelian randomization analysis can potentially guide clinical practice and improve evidence-based care, even though traditional standards often overlook the study design.

However, when applying information from research to clinical practice, it is imperative only to use rigorous research, such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses, clinical practice guidelines, randomized controlled trials, and Mendelian randomization analysis.5,6

3) Biased vs. non-biased sources

Everyone has biases, and identifying one’s own bias is often important to prevent the risk of being duped by misinformation. Most biased content has an inclination toward something. If this inclination aligns with our own beliefs, it could feed into confirmation bias. Accordingly, we need to ensure the content includes all viewpoints and is not “leading” us toward one viewpoint over another.7

Biased content can often be difficult to identify. However, you can quickly scan an article, blog post, newsletter, etc., and identify a few things that can indicate potential bias. Some considerations include:7

- Does the site where the content is published sell anything (i.e., books, supplements)? If so, consider the possibility it may be biased.

- Does the content cite valid, evidence-based references that are peer-reviewed? If not, consider the possibility it may be biased.

- What are the author’s credentials, qualifications, or expertise? If the author is writing about a topic they have no educational background in, consider the possibility it may be biased.

- Have multiple studies confirmed the assertions? In other words, have multiple studies replicated the same results? If not, consider the possibility it may be biased.

- Is the tone neutral or emotionally driven? An emotionally driven tone can sometimes indicate bias.

- Is there more than one point of view presented, or is it one-sided? One-sided content that ignores evidence that contradicts the assertion being made leaves the possibility for bias.

- Who funded the study? Are there any conflicts of interest? Funding and conflicts of interest do not always equate to bias, but it is worth scrutinizing the content if either of these are identified.

4) Does the author have a history of retractions?

Having research retracted isn’t always due to nefarious actions. Sometimes, simple mistakes are made – we are all human. However, if the author has a history of retractions, it can safely be assumed the authors are either incompetent or they are being nefarious in their research methods.

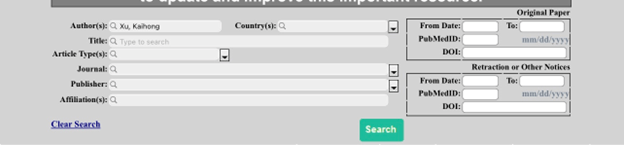

There is an amazing database that provides insight into retracted research. Not only can you ensure the author doesn’t have multiple retractions, but you can also ensure you won’t be citing a retracted study. The database is called the Retraction Watch Database.

The database allows you to search by author name or title. You can also search by the article title, article type, journal, publisher, country, and/or affiliations.8

Here is an example of what a search looks like:

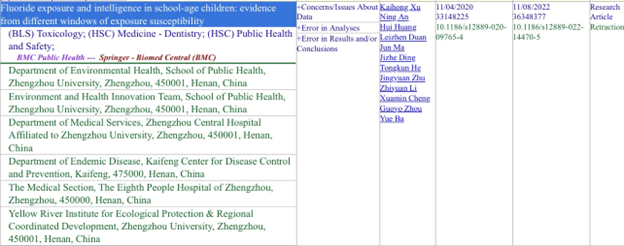

The search results identify the reasons for the retraction. In the example provided above, the reasons include concerns or issues with the data, errors in analysis, and errors in the results and/or conclusion. It also provides the names of all the authors and their affiliations.

This is an extension in the peer-review process to ensure articles published in reputable journals meet the robust requirements to be published. Even when poor-quality research makes it through the peer-review process, it can continue to be scrutinized and later retracted.

This is important because sometimes, what seems to be compelling evidence that influences patient care is published, but it may later be retracted. Our duty as health care providers is to provide evidence-based patient care. Being aware of such retractions, especially in our own field of expertise, ensures we are providing care based on valid, robust evidence.

5) Is the journal predatory?

Not all scientific journals are created equal. Did you know anyone can start a “scientific journal?” You and I could do it right now. There is no one policing this at all.9

A predatory journal is a journal that solicits articles from researchers through practices that exploit the researcher by pressuring them to publish. Many of these are “pay-to-publish” journals without a rigorous peer-review process, among other fraudulent actions.10

How can you ensure you get information from a reputable journal, not a predatory one? Well, this guy named Jeffrey Beall created a list of predatory journals that he classified as potential, possible, or probably predatory scholarly open-access publishers. The list is accessible here.11

Though Beall’s list is widely used by scholars, some argue that you should use caution when referring to it because it has not been updated since 2021. This means there could be predatory journals that have not been identified or journals that remain on the list after improving their practices. Knowing the limitations of Beall’s list, use it with caution. It is not an updated and comprehensive list.12

Another resource to vet potential predatory journals is through the website Predatory Journals. This website has an up-to-date list of both predatory publishers and predatory journals. For years, Beall’s list was the go-to resource to identify potential predatory journals. I, myself, used it regularly. However, the Predatory Journals website is my preferred resource now because it is kept up to date.13,14

6) Is the full text available?

From time to time, someone will cite a study to support a claim in their article, and when I start fact-checking, it becomes clear that the author only read the abstract and not the cited reference in its entirety. I cannot stress this enough: Never, never just read the abstract and use it as evidence.

You must read it in its entirety to first know if the research is relevant and that the results are applicable to the topic you are referencing. Additionally, the full text needs to be read because many factors need to be considered before implying the results are sound. When referencing studies, some of those factors to consider include:4,15,16

- Is the study design appropriate to answer the research question?

- Did the study design include adequate control and variables?

- Are the data collection methods reliable and valid?

- Is the sample size large enough to avoid false outcomes and allow the results to be replicated?

- Are the results statistically significant?

- Do the limitations of the study affect the interpretation of the results?

- Are there any potential sources of bias?

- How do the results and key findings fit existing research?

On the other hand, certain articles are behind a paywall, and the full text is unavailable, making it quite difficult to access. However, some options could allow you full access to articles behind a paywall. For example, there are browser extensions you can add, such as Unpaywall and Open Access Button, that will allow you to legally access PDF files of articles that are behind a paywall for free.17

Unfortunately, not all articles behind a paywall are accessible through these extensions. If you find you can’t access an article in its entirety, the next best option is to find an alternative article that you can access. This choice isn’t always the most favorable, but it is a better choice than using an abstract as evidence.

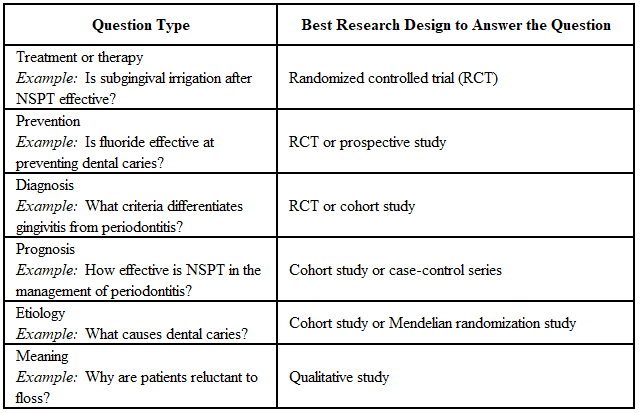

7) Identify the appropriate study design to answer your question

When reading scientific literature, the easiest way to ensure what you are reading is robust evidence is to stick to systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses could have limitations, though. For instance, if all the studies included have a high risk of bias, that could contribute to a biased conclusion. However, generally, that is addressed in the review conclusion, taking a lot of the work out of the vetting process.4

What happens when a systematic review and meta-analysis aren’t available to answer the question you have? This is when we must rely on primary or preliminary studies. However, this gets tricky because these studies often get misinterpreted by readers.

We need to understand which study design is appropriate to answer the questions we have.

Ensuring you use the correct study design will improve your understanding of the research you are reviewing while also giving you useful information.

8) Is there scientific consensus?

The term “scientific consensus” was wildly misinterpreted during the pandemic, and that misinterpretation has remained. A lot of people believe that a scientific consensus is a large group of scientists that all arbitrarily agree something is true. However, a scientific consensus is a large body of robust evidence supporting each study’s findings. The scientists’ agreement is simply a byproduct of the robust evidence.18

Knowing if there is scientific consensus on a topic is important to avoid being duped by an outlier. If you have 1000 scientists all in agreement that the Earth is round, yet one outlier says, “No, the Earth is flat,” generally, this means that the outlier is likely biased or just outright wrong.

You don’t want to fall into the trap of believing you are an independent thinker or possess some higher-powered critical thinking skills than experts in a specific field because you are going against scientific consensus.

We experience this in our clinical careers, for example, patients who believe dental care during pregnancy isn’t safe or those who refuse to get restorative treatment completed because they think it is some kind of money grab. Beyond being frustrating, it can harm the patient’s health.

Therefore, if there is scientific consensus, finding a single study that refutes that consensus is not the evidence you may believe it to be. It is likely simply an outlier that has no validity.

In Closing

As health care providers, we are tasked with bringing current evidence-based information and care to our patients. Misinformation and disinformation spread rapidly and can be difficult to refute in the short time we have with patients.

Therefore, the best course of action is to dispel misinformation at the source. Before you smash the share button when you see something on social media, take the time to vet it. Ensure the information you will be sharing is accurate, up-to-date, and free from biases.

If you can’t confirm the information is accurate, consider scrolling past rather than sharing something questionable. Though your efforts may seem trivial, every little bit helps when you are fighting a misinformation machine.

Brandolini’s law states that the amount of energy needed to refute misinformation is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.19 Accordingly, it is going to take a village, and every little contribution will help. Your voice may seem small, but it is powerful.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Words We’re Watching: ‘Infodemic.’ (n.d.). Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/words-were-watching-infodemic-meaning

- Infodemic. (n.d.). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic

- How Recent Is Recent for Good Referencing? (2022, February 9). Next X(G)eneration Referencing. https://nxref.com/recent-research-works-for-good-referencing/

- Evidence-Based Practice in Health. (2023, July 24). University of Canberra. https://canberra.libguides.com/c.php?g=599346&p=4149721

- Davies, N.M., Holmes, M.V., Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian Randomisation Studies: A Guide, Glossary, and Checklist for Clinicians. BMJ. 2018; 362: k601. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6041728/

- Mendelian Randomization. (n.d.). University of Bristol. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/integrative-epidemiology/research/mendelian-randomization/about-mendelian-randomization/

- Evaluating Sources. (2024, October 17). Franklin University. https://guides.franklin.edu/sources/bias

- Retraction Watch Database User Guide. (2024, October 23). Retraction Watch. https://retractionwatch.com/retraction-watch-database-user-guide/

- Johnson, J. (2023, June 26). A DIY Guide to Starting Your Own Journal. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/diy-guide-starting-your-own-journal

- Understanding Predatory Journals. (2024, October 8). University of Massachusetts Lowell Library. https://libguides.uml.edu/c.php?g=563165&p=3877249

- Beall’s List of Potential Predatory Journals and Publishers. (2021, December 8). Beall’s List. https://beallslist.net

- Beall’s List. (n.d.). Sacred Heart University. https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=1310982&p=9635666

- The Predatory Publishers List. (2024, March). Predatory Journals. https://predatoryjournals.org/predatory-publishers

- The Predatory Journals List. (2024, March). Predatory Journals. https://predatoryjournals.org/predatory-journals

- George, T. (2024, May 9).What Are Credible Sources & How to Spot Them | Examples. Scribbr. https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/credible-sources/

- Althubaiti, A. Sample Size Determination: A Practical Guide for Health Researchers. J Gen Fam Med. 2022; 24(2): 72-78. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10000262/

- What Is Unpaywall? How Do I Use It? (2022, April 27). American University. https://answers.library.american.edu/faq/247967

- Burt, M. (2020, May 15). What Is Scientific Consensus, and How Do We Achieve It? Virginia Tech. https://globalchange.vt.edu/news/news-stories/2019-20-news/what-is-scientific-consensus-and-how-do-we-achieve-it.html

- Williamson, P. Take the Time and Effort to Correct Misinformation. Nature. 2016; 540: 171. https://www.nature.com/articles/540171a