Dental hygienists see a range of oral lesions on any given day in clinical practice that takes us back to the pages of our oral pathology books. The ability to identify and differentiate oral lesions is one of the most important skills we learn. Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a very common dermatologic disease which can affect the skin and oral mucosa and is one of the most frequent oral pathologies encountered by dental hygienists. Like most oral pathologies, early, correct diagnosis is very important to manage oral lichen planus and treat flare-ups successfully.

The term “lichen” is derived from the familial name of algae and fungi that are sprawling by nature, and “planus” is Latin for flat.4 The name of this oral pathology can be somewhat misleading since it may present in several different ways. The etiology of oral lichen planus is not completely understood, but it is believed to be related to a cell-mediated, auto-immune disease which can cause inflammation, burning, and soreness intraorally. Oral lichen planus is commonly found on buccal mucosa, gingiva, and tongue. It is not caused by an infection, it is not transmissible, and is not curable at this time.6

OLP affects approximately 1-2% of the total population. It is most common in middle-aged adults, and women are two times more likely to be affected than men.4,6 There is thought to be a correlation with emotional factors, like anxiety and stress, and the presentation of oral lichen planus lesions.2 The most accepted explanation of this pathology is related to changes in cell-mediated immunity. These changes result in an abnormal response to self-antigens causing T-cells to accumulate in the lamina propria adjacent to the epithelium resulting in rupture of the basal membrane.2 In short, infiltrating T-cells cause apoptosis (cell death) of basal cells in oral epithelium after encountering antigens.5 The specific antigen that causes this reaction has not been identified, making OLP tough to classify as autoimmune.

To help a patient to treat and manage oral lichen planus, it should first be confirmed with a definitive diagnosis. Leukoplakia, pemphigus, mucous membrane pemphigoid, erythematous candidiasis, and chronic ulcerative stomatitis can all present with similar characteristics to OLP. Dental hygienists should be aware that concurrent candidiasis infections often accompany OLP, and may make treatment more difficult if not recognized.4 Frictional keratosis (cheek chewing) creates white, thickened buccal tissue in linear patterns like oral lichen planus, and lupus erythematous appears with similar striations, but from a central focus and with a less symmetrically distributed pattern.

Localized lichenoid reactions may also occur in response to dental restorative materials, and will appear near newly placed restorations. Lichenoid drug reactions or medication-induced lichenoid mucositis may also appear with a history of new drug intake; these reactions are usually unilateral.5 Antibiotics, antihypertensives, diuretics, anti-malarial, and NSAIDs have all been found to cause these types of reactions.1 Patients with painful symptoms should have a biopsy to confirm OLP and proceed with management.

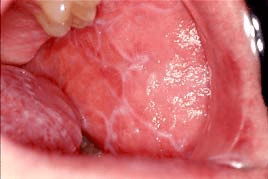

Oral lichen planus is categorized as reticular or erosive. It may present as papular, plaque-like, atrophic or bullous. Reticular oral lichen planus is more common and is often asymptomatic. Lesions may come and go over time with trademark lace-like networks of fine lines named Wickham’s Striae that show up on dorsal and lateral tongue surfaces, posterior buccal mucosa, gingiva, and sometimes palatal tissue.4 As long as a patient is asymptomatic with reticular OLP, no treatment is necessary.

Reprinted from https://www.aaom.com/oral-lichen-planus3

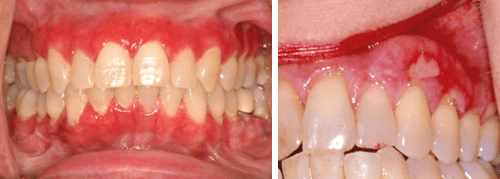

Erosive oral lichen planus involves more ulcerative lesions which cause severe pain and burning sensations.2 Erythematous areas with central ulcerations may appear on any mucosal surface similar to reticular OLP. A biopsy is indicated with erosive oral lichen planus for several reasons. If the ulcerated tissue is limited to the gingiva, desquamative gingivitis can be ruled out with biopsy, as well as cicatricial pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris, which have similar characteristics.4 It is also important to biopsy since some studies suggest erosive oral lichen planus may also be an early warning sign of oral cancer. Much more research is needed to confirm any correlation between OLP and oral cancer.6

There is no curative treatment currently for oral lichen planus. The aim of most treatment options available is to reduce symptoms of ulcers and facilitate healing to remission. Pharmacies may prepare treatment options as gels, ointments, creams, solutions, suspensions, sprays, and emulsions. Topical therapy in the form of solution as a rinse or spray is the presentation most frequently prescribed for the treatment of symptomatic OLP lesions and allows ease of application with the least adverse effects for patients. Duration of treatment is relative and is normally continued with regular follow-up until there is a reduction in symptoms and remission of the lesion.2

Corticosteroids are commonly the first line of defense with OLP working to modulate inflammation and immune response; different potencies may be used depending on the severity of the case. Topical corticosteroid drugs range from mid-potency triamcinolone acetonide to highly potent fluorinated corticosteroids like fluocinonide acetonide and disodium betamethasone phosphate. Super potent halogenated corticosteroids are also available as clobetasol. Patients with widespread oral lichen planus may be prescribed high/super potent corticosteroid mouth rinses or direct intralesional injections. Prednisone is also commonly used systemically after all topical options have failed. It is reserved for obstinate erosive or erythematous lichen planus and should be used at the lowest possible dose for the shortest duration. Prolonged use of local or systemic corticosteroids may cause severe side-effects.5

While corticosteroids are the most common course of treatment of oral lichen planus, but there are several other immunosuppressants and immunomodulatory drug options. Calcineurin inhibitors, cyclosporin, tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, retinoids, dapsone, mycophenolates, and efalizumab may also be prescribed depending on the patient situation.5

There are some non-pharmacological modalities to treat and manage OLP as well. Most laser therapies destroy superficial epithelium that contains target keratinocytes by protein denaturation. Deeper penetrating diode lasers destroy underlying connective tissue and the inflammatory component. This type of therapy has shown promising effectiveness but requires more research and trials.5

Photodynamic therapy uses a photosynthesizing compound like methyl-blue activated by a laser or selected wavelength of visible light. The goal of this treatment is to cause apoptosis and encourage healing through tissue regeneration. These therapies have shown less than or comparable results to corticosteroids for treatment of oral lichen planus, but management effectiveness is still in question.1,2,5

Patients with minimal symptoms or only occasional occurrences of oral lichen planus may want to try green tea for its anti-inflammatory and chemopreventive properties which may reduce the incidence of OLP. In one study, aloe vera was also shown to be more effective than triamcinolone acetonide. 60% of a 64-person study were treated with a .4ml 70% aloe vera concentration had complete resolution of pain and no adverse effects at a 12-week re-evaluation.2

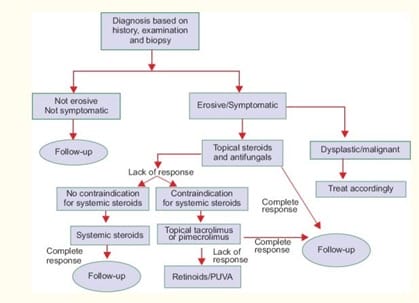

The diagram below outlines a systematic protocol for oral lichen planus and may help to find an effective treatment plan.5

Patients with suspected oral lichen planus should avoid alcohol, smoking, or foods that irritate the oral tissue. Dental hygienists are often first to see oral pathologies and should collect all pertinent information from health history, risk factors, and biopsy results to correctly identify oral lichen planus. Only then will management and treatment be as effective as possible.

References

- Akram Z, Javed F, Hosein M, et al. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2018;34:167–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpp.12371

- Borba Filla J., Fontanelli A., Brown M.A., Machado M.A.N. Treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: a literature review. Pol Otorhino Rev 2016; 5(1): 30-35

- Burkhart, N. (2013, September). Oral Lichen Planus. Retrieved December 9, 2018, from https://www.aaom.com/oral-lichen-planus

- Darby, M. L., & Walsh, M. M. (2010). Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice (3rd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders/Elsevier.

- Lavanya, N., Jayanthi, P., Rao, U. K., Ranganathan, K. (2011). Oral lichen planus: An update on pathogenesis and treatment. Journal of oral and maxillofacial pathology: JOMFP, 15(2), 127-32.

- What You Need to Know About Lichen Planus. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/dermatology/lichen_planus_134,220