Change is inevitable. Without change, there is no movement forward. The process of change is not always an easy one. As primary health-care providers, dental hygienists are known as health promotion specialists and behavior change motivators.

Dr. Alfred Fones originally developed the profession of dental hygiene to be educators and clinicians. Dr. Fones believed in the value of health education to effectively change the course of dental disease. Along with that health education, he also believed in the effective mechanical removal of oral biofilm, calculus, or tartar.1 Dental hygienists are unique in that not only are we providing highly important education, but we are also clinicians providing therapeutic, clinical procedures that benefit the overall health outcomes of patients.

It is important for dental hygienists to understand and apply the use of behavior change theory within the everyday care and motivation of patients. There are four theories that can be used interchangeably within the clinical practice of dental hygiene.

- The health belief model

- The transtheoretical model

- The Lewin change theory

- The Lean system

Health Belief Model

This model is based on the understanding that a person will take a health-related action if that person:

- Feels that a negative health condition can be avoided

- Has a positive expectation that, by taking a recommended action, he/she will avoid a negative health condition

- Believes that he/she can successfully take a recommended health action.2

It is important to design patient education with this model in mind. This is part of the bigger picture as to why a person should be seeking dental hygiene care in the very beginning. Educating younger patients is the best example of this model. Practitioners discuss the overall effects of home-care practices in the mouth and the outcomes that can be changed if certain health behaviors are adopted. For example, brushing twice a day and cleaning interdentally daily can reduce the risk of dental caries factors.

This conversation needs to occur to ensure that patients understand the risks of not taking action to improve oral health. Again, this is central to the purpose of the dental hygienist and why Dr. Fones developed this profession. The health belief model was developed in the 1950s by social scientists in the U.S. Public Health Service. The model was developed to help understand the failures of people to adopt disease prevention strategies or screening tests for the early detection of disease.3

The Health belief model was derived from psychological and behavioral theory with the foundation of two components.3

- The desire to avoid illness, or conversely get will if already ill.3

- The belief that a specific health action will prevent, or cure, illness3

The HBM consists of four original constructs, and two more were added for the purposes of research.3

- Perceived susceptibility − This refers to a person’s subjective perception of the risk of acquiring an illness or disease. There is wide variation in a person’s feelings of personal vulnerability to an illness or disease.3

- Perceived severity − This refers to a person’s feelings on the seriousness of contracting an illness or disease (or leaving the illness or disease untreated). There is wide variation in a person’s feelings of severity, and often a person considers the medical consequences (e.g., death, disability) and social consequences (e.g., family life, social relationships) when evaluating the severity.3

- Perceived benefits − This refers to a person’s perception of the effectiveness of various actions available to reduce the threat of illness or disease (or to cure illness or disease). The course of action a person takes in preventing (or curing) illness or disease relies on consideration and evaluation of both perceived susceptibility and perceived benefit, such that the person would accept the recommended health action if it was perceived as beneficial.3

- Perceived barriers − This refers to a person’s feelings on the obstacles to performing a recommended health action. There is wide variation in a person’s feelings of barriers, or impediments, which lead to a cost/benefit analysis. The person weighs the effectiveness of the actions against the perceptions that it may be expensive, dangerous (e.g., side effects), unpleasant (e.g., painful), time-consuming, or inconvenient.3

- Cue to action − This is the stimulus needed to trigger the decision-making process to accept a recommended health action. These cues can be internal (e.g., chest pains, wheezing, etc.) or external (e.g., advice from others, illness of family member, newspaper article, etc.).3

- Self-efficacy − This refers to the level of a person’s confidence in his or her ability to successfully perform a behavior. This construct was added to the model most recently in the mid-1980s. Self-efficacy is a construct in many behavioral theories as it directly relates to whether a person performs the desired behavior.3

When thinking about the HBM, it is very apparent that Dr. Fones was well before his time before the development of the health belief model in the 1950s. Dr. Fones made the assumption that by developing an auxiliary member of the dental profession that provided education, they would also be impacting the oral health outcomes of dental patients.

There are many limitations of the HBM and for the purposes of this article, I will include one of the limitations. The HBM is more descriptive than explanatory; it does not include any strategies for behavior change. For the HBM to be most effective, it must be integrated with other models that account for environmental consideration and strategies for behavior change.

Transtheoretical Model

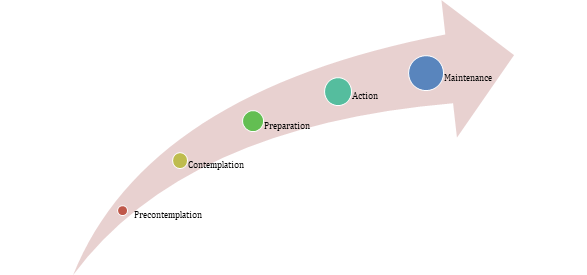

The second change theory to consider is the transtheoretical model (TTM), or better known as stages of change. The TTM can and should be used in the dental hygiene appointment to determine the readiness of a patient before receiving health education.

The stages of change are:

- Precontemplation − Not ready to take action

- Contemplation − Getting ready to take action

- Preparation − Ready to take action in the immediate future

- Action − Have made significant steps or modifications in last six months

- Maintenance − Have made significant modifications and working on preventing relapse4

Studies of behavior change have found that individuals move through a series of stages when modifying behavior. This can occur over a course of time rather than in one initial moment. While the time a person can stay in each stage is variable, the tasks required to move to the next stage are not. Certain principles and processes of change work best at each stage to reduce resistance, facilitate progress, and prevent relapse. TTM recognizes change as a process that unfolds over time, involving progress through a series of stages.4

During the dental hygiene appointment, a series of open-ended questions is an excellent way to determine the stage of change. The process of asking open-ended questioning can be done with techniques of motivational interviewing combined with excellent listening skills.

The best example that I can give is when I first approach a patient, update their medical history, take blood pressure, and then determine if the patient has any questions or concerns for their appointment that day. I simply ask, “ Tell me how (Fones, 1934) you feel you have been doing with your oral hygiene routine since we last met?”

Motivational interviewing techniques will help to identify the stage of change. By using a question that is prompted by curiosity, you open many doors. When listening very carefully, a common answer is this: “Not very well. You are probably going to be upset with me.”

Ask the patient to explain why he or she doesn’t think they haven’t done very well. I will communicate that there is no judgment. I myself struggle at flossing. It is important to establish a safe space that is judgment-free, allowing a patient to speak openly about their struggles and to establish if they are ready to make changes.

Patients who are in the precontemplation stage will immediately disengage. That is a sure sign that now is not the time to try to change their routine. However, that does not mean you should not educate them. It is a time to tailor the message differently. At that moment, it is important to meet the patient where they may be and be respectful of where they may be. It’s like that old saying, “you can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make them drink.”

There is one other change theory that can come into play during a dental hygiene appointment. Let’s step back into the appointment again. The patient identified that they hadn’t done very well with flossing, and they state they need to do better. Bingo! They are in a stage of change to either contemplate that change in habit or are ready to prepare for that change. This is where the Lewin change theory can come into play.

Lewin Change Theory

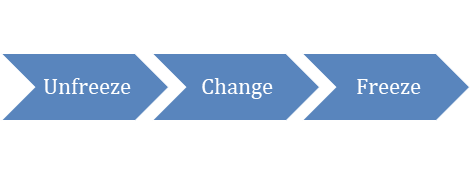

The Lewin change theory is a three-step process of behavior modification. Unfreeze, change, and refreeze is one of the simplest ways to explain this theory. This change theory of nursing was developed by Kurt Lewin, who is considered the father of social psychology. This theory is his most influential theory. He theorized a three-stage model of change known as an unfreezing-change-refreeze model that requires prior learning to be rejected and replaced.5,6

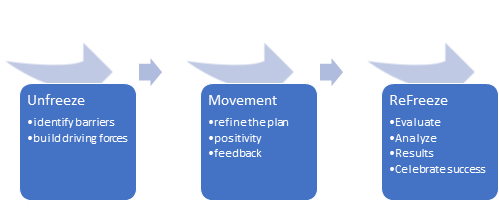

The Lewin change theory has three major concepts: driving forces, restraining forces, and equilibrium. Driving forces are forces that push in a direction that causes change to occur. These forces facilitate change because they push the patient in a desired direction.

They cause a shift in the equilibrium towards change. Restraining forces are those forces that counter the driving forces. Restraining forces hinder change because they push the patient in the opposite direction, causing a shift in the equilibrium that opposes change. Equilibrium is a state where driving forces equal restraining forces, and no change occurs. Equilibrium can be raised or lowered by changes that occur between the driving and restraining forces.5,6

We should review the Lewin change theory before we move on with our hypothetical patient. The first step, unfreezing, is the process that involves finding a method of making it possible for people to let go of an old pattern that was somehow counterproductive. At this step, it is necessary to overcome the strains of individual resistance.

Three methods can lead to the achievement of unfreezing. The first is to increase the driving forces that direct behavior away from the existing situation or status quo. Second, decrease the restraining forces that negatively affect the movement from the existing equilibrium. Thirdly, find a combination of the first two methods.

The change stage, which is also called “moving to a new level” or “movement,” involves a process of change in thoughts, feeling, behavior, or all three, that is in some way more liberating or more productive. The refreezing stage is establishing the change as the new habit so that it now becomes the “standard operating procedure.” Without this final stage, it can be easy for the patient to go back to old habits.5

The Lewin model is typically used to develop strategic change within an organization. However, this model can be applied to patient care, particularly when considering making a long-term strategic plan of care for continuing care patients. This would be important to document this strategic plan within the patient’s electronic health record for future access and future continuing care visits.

When in the unfreezing step, it is time to identify barriers or resistance and begin building new driving forces for change to occur. If the patient we have been discussing doesn’t floss, it is important to ask them what the barriers may be. This conversation can be initiated by stating, “Tell me why you think you don’t floss regularly now?”

Once the barriers are identified, then we can begin to build a plan for better success in the future. I have found most of the time patients either struggle with establishing the habit of flossing or they struggle with the actual floss itself, or simply don’t like string floss. This provides a moment when alternative habit-building practices can be discussed, or a different tool can be recommended to increase their chances of home care success and to essentially reach the goal of a stable and healthy oral health status.

Establish the changes needed to address their barriers and then ask the patient if they have an interest in those changes. If they respond positively to those suggested solutions to their barriers, then move to the “refreeze” stage and make note of those goals in the electronic health record. These can be revisited at the next continuing care visit. When a patient returns for continuing care reassessment, analyze home care practices again, and most importantly, celebrate the patient’s successes. If the patient was not successful, then begin again and unfreeze to reinitiate the process.

The Lean System

The Lean system can be combined with the Lewin change theory. The Lean system is a people-based system, focusing on improving processes and supporting people through standardized practices to create process predictability, improved process flow, and ways to make defects and inefficiencies visible to empower people to take action at all levels.7,8

Both the Lewin and the Lean system can be combined at this point in the appointment. Health care has taken on the process of shame and blame, and the Lean system creates a blame-free and shame-free environment.

The Lean approach attacks the process and not the person, creating a no-blame culture. This process builds trust and moves the process into a transformative stage, measures improvement, implements, and sustains the changes. Using the best of both the Lewin and Lean approaches can help facilitate patient-provider collaboration and problem-solving.6

| Lewin Stages: Examples of concepts and processes | Lean System |

Unfreeze

|

Plan

|

Change

|

Do

|

Freeze

|

Check

|

Back to our hypothetical patient. Remember, they identified that they hadn’t done well with flossing, and they should be doing better. Create curiosity by asking the patient, “Tell me more about how you feel you could do better flossing.” Motivational interviewing techniques should be used at this time. These are curiosity building statements or questions that prompt the patient to verbalize the knowledge they have of how they feel they should proceed to improve their oral health practices.

Most of the time, patients will already know the answers themselves. By creating an environment of curiosity, then you become more of a coach in this conversation to help them explore their thoughts about flossing. Once the patient verbalizes what the changes should be to meet their desired outcomes, start by saying to the patient, “Would it be okay if we unpack this for a minute, and we review the reasons you have mentioned?” It is important to get permission from the patient. Patient buy-in is essential to the success of the conversation. Creating a trusting and positive environment is essential to success.

When permission is given to proceed to address the issue at hand, move forward into discussing what home-care level or frequency may be the goal and as to what outcomes they would rather see from their home-care practices.

Most patients already have a basic knowledge of oral health, gingivitis, and periodontal disease, especially if they are a continuing care patient in the dental practice. They likely have heard it all before. The change in your message this time will likely be more impactful because of the removal of the blame and shame. The creation of a trustful environment allows the patient to become vulnerable enough to discuss this with you. Creating an environment of trust will help promote better success.

When the desired outcomes are expressed, move into designing the process for them to reach those desired outcomes. Maybe the patient indicated that they always have bleeding, and they would like to reduce the occurrence of the bleeding. Processes should be set based on the patient’s identified goals. If the hygienist sets the goals, the process would not be as successful. There needs to be patient ownership of the goals. Then this is the force that shifts the equilibrium for health behavior change to be successful for patients.

Once the goals and processes are determined, then proceeding to the third step of the process, freezing until the next preventive care visit. Of course, it would be unnecessary to explain these change theories to patients. The process of behavior changes and the social science behind it all is not relevant to them.

However, it has been proven that periodontal patients experience success if behavior change theory is applied and used to assess compliance with periodontal treatments.8 The application of health promotional theories and social science does impact successful outcomes for dental patients.

As dental hygienists, we are continually multitasking while we treat patients. Dental hygienists are assessing risks for diseases and inflammation. At the same time, dental hygienists remain in the mode of health promotion specialist, educator, and motivator.

This is another reason why the proper amount of treatment time should be allocated to patient care on a continual basis. Sadly, the business of dentistry is shortening the allocated patient treatment time, which will ultimately discontinue the health promotional education within continuing care appointments. Without including education and behavior modification, the result could be poorer health outcomes for patients.

There is a method to our madness as hygienists. These health models are the strategies behind our recommendations to patients. They can be used together or separately, depending on the patient you are working with.

Is this really where we want oral health care to move? If oral health care or health care in general moves towards outcome-based or value-based reimbursement, we could be creating a perfect storm by shortening treatment time and removing valuable educational instruction for patients. The outcome is likely to be poorer health, not improved health.

I challenge dental hygienists to advocate for their profession and advocate for the appropriate amount of treatment time to ensure better health outcomes for dental patients and their overall total health. Patients’ lives depend on it.

Now Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Fones, A.C. Mouth Hygiene. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1934.

- Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice,Karen Glanz and Barbara Rimer, National Institute of Health, 1997.

- Behavioral Change Models. Boston University School of Public Health. Retrieved from https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modeles/SB/BehaviorialChangeTheories?behavioralChangeTheories2.html

- Prochaska, J.O., Redding, C.A., Evers, K. (2002). The Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change. In K. Glanz, B.K. Rimer and F.M. Lewis, (Eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (3rd Ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc

- Lewin’s Change Theory. Nursing Theory. Retrieved from https://nursing-theory.org/theories-and-models/lewin-change-theory.php

- Wojciechowski, E., Pearsall, T., Murphy, P., French, E. A Case Review: Integrating Lewin’s Theory with Lean’s System Approach for Change. Online J Issues Nurs. 2016; 21(2): 4. DOI:10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No02Man04.

- Liker, J.K. (2004). The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Toussaint, J.S., Gerard, R.A. (2010). On the Mend: Revolutionizing Healthcare to Save Lives and Transform the Industry. Cambridge, MA, USA: Lean Enterprise Institute.

- Emani, S., Thomas, R., Shah, R., Mehta, D.S. Application of Transtheoretical Model to Assess the Compliance of Chronic Periodontitis Patients to Periodontal Therapy. Contemp Clin Dent. 2016; 7(2): 176–181. DOI:10.4103/0976-237X.183068.