What is full mouth debridement and when exactly are we supposed to do it? Ask a variety of clinicians, and you will receive a variety of answers. Does it pertain only to scaling above the gingival margin, or can we go below? Is it an acceptable step prior to scaling and root planing or is it simply a “bloody prophy”? Can we anesthetize the soft tissue? Can we polish during the appointment? Can we do it on the same day as an exam? Is it an acceptable procedure to do on children? What follow-up treatment is required? Even a simple internet search unleashes a deluge of varying definitions from “experts” on the subject. With the recent release of the CDT 2018 code revisions, it is the perfect time to take a step back and review the many lives of full mouth debridement (FMD).

As a millennial hygienist, FMD was only mentioned briefly to me during hygiene school as a thing of the past. “You will rarely use it,” the instructors claimed. Within my own first year of clinical practice, it became quickly apparent that indeed most new hygienists rarely ever used it. Seasoned hygienists and dentists were another story, however — potentially overusing and even incorrectly coding it. After working with countless dental teams over the last decade, I am all the more convinced that clinicians are regularly confused as to the purpose of the procedure and often conceive of it as a gray area in clinical dentistry. I typically see it used in the following scenarios:

- As a treatment placeholder for patients needing more than prophylaxis but do not yet qualify for non-surgical periodontal therapy

- When patients refuse necessary periodontal therapy but still request some kind of treatment

- As a profit maximizer for determined employers

- When it is difficult to complete an exam due to the presence of plaque and calculus

Out with the old, in with the new

But it is time to shake off your previous assumptions and definitions of FMD and begin anew. In general, “debridement” means the removal of damaged tissue or foreign deposits from a wound. It is therefore important to differentiate between FMD as a particular procedure and our common vernacular that often uses the words “debride” and “scale” interchangeably. Obviously, this can be confusing since a clinician “debrides” teeth during preventive and therapeutic procedures as well as when fully utilizing FMD.

Recently, the American Dental Association released the CDT 2018 Dental Procedure Code Book which offers the following definition of FMD:

D4355 full mouth debridement to enable a comprehensive oral evaluation and diagnosis on a subsequent visit. Full mouth debridement involves the preliminary removal of plaque and calculus that interferes with the ability of the dentist to perform a comprehensive oral evaluation. Not to be completed on the same day as D0150, D0160, or D0180.

Thus, if a patient presents with a mouth so full of plaque and calculus that it is difficult to see the hard and soft tissues, probe the sulcus, or explore the dentition, then the use of FMD may be justified. The revised code clarifies that the patient must return on another day for the completion of a comprehensive oral evaluation, a problem-focused oral evaluation, or a comprehensive periodontal evaluation.

So, can we anesthetize the gingiva, scale subgingival deposits, or polish during FMD? Yes. We do what is needed to remove the plaque and calculus. Can we perform it on children? Yes. The definition is not age-specific. It also does not determine the need for follow-up treatment because it is not classified as a therapeutic procedure. The implementation of D4346 — a therapeutic procedure for the treatment of gingivitis — only helps to clarify that FMD is not simply a placeholder treatment for patients needing more than a prophylaxis.

The origins of FMD

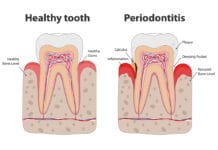

FMD, sometimes referred to as “gross scale,” originated when the prevailing theory was that calculus caused periodontal disease and when clinicians regularly performed “gross scale/fine scale” treatments over multiple appointments. We now understand calculus as an irritant and know that partially removing it allows the tissue to tighten up, creating difficult access to the sulcus. We have since learned that biofilm and host-factors play prominent roles in periodontal disease and now maintain that the standard of care is to “scale to completion.”

Better but not yet perfect

The revised definition of FMD is not yet perfect. For example, consider a fundamental aspect of the oral evaluation: periodontal probing. According to the revised definition, proper FMD will include removing enough plaque and calculus to allow a precise measurement of the sulcus. The problem lies here — probing a sulcus filled with subgingival calculus is like trying to measure a clogged pipe — any existing calculus will prevent a probe from properly aligning with the tooth, which leads to incorrect measurements. Because the sulcus is measured visually and in millimeters, there is an understandable high probability of error. The most accurate measurements will always be on a calculus-free tooth. Per the CDT definition, one must assume that complete removal of subgingival calculus is necessary during FMD in order to obtain an accurate assessment. But complete removal is not possible, for that only takes place during subsequent therapeutic procedures.

Another flaw lies within the very definition of what a CDT code is, for the ADA asserts that “The purpose of the CDT code is to achieve uniformity, consistency, and specificity in accurately documenting dental treatment1.” The key word here is “treatment.” Instead of relying on treatment codes to define diagnosis, dental clinicians must begin to ask themselves “What is the diagnosis?” To help with this issue, stakeholders are presently working to finalize and implement SNODENT — a system that will provide standardized terms for describing dental disease2. However, it has never been more important for hygienists to realize that diagnosis remains a critical part of our daily practice3.

Moving forward

Out with the old, in with the new! Even though FMD, as we know it today, is not perfect, thanks to the newly revised and clarified definition, it is no longer a gray area in clinical dentistry. Although the code may continue to be revised and subsequently have many more “lives,” full mouth debridement will be a vital tool in the dental clinician’s ever-changing toolbox for the foreseeable future.

NOW READ: Why You’re Missing Out if You Aren’t Using an Intraoral Camera

References

- https://www.ada.org/en/publications/cdt

- https://www.ada.org/en/member-center/member-benefits/practice-resources/dental-informatics/snodent

- https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/7111_Dental_Hygiene_Diagnosis_Position_Paper.pdf