Historical medicine and dentistry are fascinating. It gives a starting point that can be traced to current treatment modalities and prevention, as well as a basis for a better understanding of systemic and complex diseases.

The “discovery” made by Wilhelm Fredrick von Ludwig is one of great importance. During his lifetime (1790-1865), many people died from what he described as “a fast-spreading, nearly always fatal gangrenous induration of the connective tissues of the neck and floor of the mouth.”1 We refer to this infection today as Ludwig’s angina.

Ludwig’s angina is a rare condition, not often seen today. However, when it does occur, it is still potentially life-threatening and requires immediate medical intervention. Though fatality rates associated with Ludwig’s angina have vastly improved compared to historical accounts, mortality is still associated with the condition today.2

Etiology

The most common cause of Ludwig’s angina is dental infections; mandibular molar infections account for 90% of cases. However, maxillary infections, as well as injuries, can contribute to the condition. Oral piercings, tongue injuries, traumatic intubation, peritonsillar abscess, as well as sialolithiasis have been implicated in the etiology of cases of Ludwig’s angina.

Some individuals are at a higher risk of developing Ludwig’s angina due to predisposing factors such as diabetes, oral malignancies, untreated dental caries, alcoholism, malnutrition, and immune-compromised status. However, most cases of Ludwig’s angina develop in previously healthy patients.3

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of Ludwig’s angina is usually polymicrobial and includes species of bacteria that are found in the oral flora. The most common organisms implicated in the condition include Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Pepto streptococcus, Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, and Actinomyces.

The infection spreads toward the tongue due to less bone density on the lingual side of the tooth. It then invades the sublingual space and progresses quite quickly to the submandibular space.3,4

Ludwig’s angina has four significant signs to look for in patients:

- Bilateral involvement of multiple deep tissue spaces

- Gangrene with serosanguinous, putrid infiltration with little or no obvious pus

- Involvement of connective tissue, fascia, and muscles but not glandular structures

- Spread via facial space rather than the lymphatic system5

Case Reports

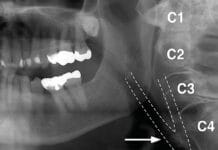

A case report of an 11-year-old child was examined. The patient presented with fever and bilateral submandibular swelling that progressed quickly to submental swelling (see Image 1). No underlying medical conditions were reported.6

Image courtesy Simsek, et al.6

(CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

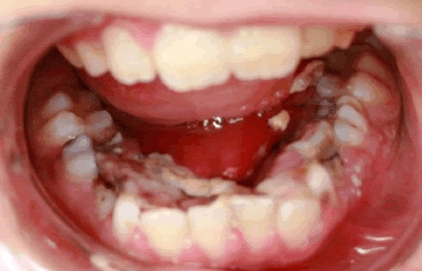

The patient had radicular infections on both sides of the mandible, evident on a panoramic radiograph (see Image 2). The patient needed both his first and second primary molars extracted due to gross decay. The patient was placed on IV penicillin G and metronidazole, and improvements were evident within three days. Six months post-extraction, the patient was completely healed, and no lingering effects from the infection were evident.6

Image courtesy Simsek, et al.6

(CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

In another case report, a 26-year-old female was admitted to the emergency department with bilateral swelling of the sublingual and submandibular space. The patient reported visiting a dentist, receiving a diagnosis of pericoronitis, and being given a prescription for antibiotics and analgesics one week prior, with no improvement. Ludwig’s angina was diagnosed immediately based on clinical presentation. The diagnosis was further confirmed through contrast-enhanced computed tomography.7

The patient was immediately administered one gram of cefotaxime intravenous three times a day. Exudate was cultured and determined to be Alpha hemolytic streptococcal, which indicated the need to change antibiotic therapy from cefotaxime to gentamicin.

The swelling progressed to the pharyngeal space, and imaging indicated lung damage likely associated with COVID-19. This case became more complicated due to the patient’s positive COVID-19 status. Physicians treated both COVID and Ludwig’s angina, which required ICU hospitalization as the patient’s status was declining.

After the patient was stabilized, multiple teeth were extracted, and local irrigation with metronidazole was completed twice a day for eight days. The patient also began physical therapy for trismus using the popsicle stick method. The patient was discharged after 15 days with general conditions improved.7

Treatment and Management

Ludwig’s angina can quickly obstruct the airway and spread systemically, causing sepsis. Reports of past incidents indicate progression can occur in a few hours, despite the use of antibiotics. Therefore, any swelling on the mandible is considered an emergency, and patients should be seen at the dental office or in an emergency medicine setting immediately.5,6

In the pre-antibiotic era, Ludwig’s angina had a mortality rate that exceeded 50%. Today, with antibiotics and proper treatment, mortality is down to 8%. This current figure, though, is still too high since, in most cases, this is a preventable condition.3

Early diagnosis and treatment are necessary to reduce the risk of mortality. Treatment consists of airway management, aggressive intravenous antibiotics, and in some cases, surgical drainage. Most cases of Ludwig’s angina could be prevented with routine dental care.5,6

Conclusion

Though rare, Ludwig’s angina is a life-threatening emergency requiring immediate care. During my career as a clinical hygienist, I have had one patient present with Ludwig’s angina that required hospitalization and IV antibiotics. Luckily, the patient did not require intubation or tracheotomy, which is often necessary to manage the airway. The patient had the offending tooth extracted, and improved with no further complications post-extraction. This experience inspired me to advocate for patients reporting tooth pain to be seen right away by their dentist.

I encourage all dental professionals, especially those managing the schedule, to inquire about swelling when a patient calls to report tooth pain. If the patient has swelling and your office can not accommodate the patient immediately, direct the patient to seek medical care at the local emergency department.

As mentioned, Ludwig’s angina can progress in a matter of hours. Prompt treatment is vital to prevent serious complications and, in some cases, death.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on pure education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Murphy S.C. The Person behind the Eponym: Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig (1790-1865).Journal of Oral Pathology and Medicine. 1996; 25(9): 513-515. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00307.x

- McDonnough, J.A., Ladzekpo, D.A., Yi, I., et al. Epidemiology and Resource Utilization of Ludwig’s Angina ED Cisits in the United States 2006-2014.The Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9): 2041-2044. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27734

- An, J., Madeo, J., Singhal, M. (2022, October 10). Ludwig Angina. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482354/

- Kim, D.G., Elias, K.L., Jeong, Y.H., et al. Differences between Buccal and Lingual Bone Quality and Quantity of Peri-implant Regions.Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2016;60: 48-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.12.036

- McKenna, C., Shufeldt, J. Case Report: Ludwig’s Angina. (2021, November). The Journal of Urgent Care Medicine. https://www.jucm.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/2012-7219-23-Case-Report.pdf

- Simsek, M., Yildiz, E., Aras, M.H. Ludwig’s Angina: A Case Report. J Interdiscipl Med Dent Sci. 2014; 2: 126. https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/ludwigs-angina-a-case-report-jimds-1000126.php?aid=28586

- Poorna, T.A., Lokesh, J.R., Ek, J., John, B. Ludwig’s Angina In a COVID Positive Patient – An Atypical Case Report.Special Care in Dentistry. 2022;42(1): 99-102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8662242/