Dental hygienists who perform comprehensive intraoral and extraoral exams recognize the importance of healthy labial mucosa. Dental patients may present with pathology or variations of normal pertaining to the lips, ranging from Fordyce spots and cheilitis to cancer.

Patients may not have any symptoms or only esthetic concerns, but it is important to be able to differentiate benign conditions from those that may warrant a biopsy.

Anatomy and Function

The upper lip (labium superius oris) and the lower lip (labium inferius oris) are comprised of mucosal membrane, vermillion, and cutaneous surfaces. The external carotid artery provides the principal blood supply to the lips. Motor innervation is provided by the buccal branch of the facial nerve, while the trigeminal nerve provides sensory innervation.1

The vermilion of the lips is comprised of a modified mucous membrane composed of hairless, highly vascularized, nonkeratinized, and stratified squamous epithelium. This membrane is three to five cellular layers in thickness. This surface contains no hair follicles, salivary, sweat, or sebaceous glands.1

The lips intersect at the commissure, where several muscles involved in lip movement attach. The modiolus, a fibromuscular tissue structure, includes the orbicularis oris, levator and depressor anguli oris, risorius, platysma, buccinator, and zygomaticus major muscles that facilitate mastication, phonation, and facial expression. The principal muscle of the lips is the circumferential orbicularis oris, which functions as a sphincter for the oral cavity. Adequate function of the orbicularis oris is needed for the closure of the mouth, chewing, and creating an oral seal.1

The lips play a critical role in breastfeeding by creating a funnel shape to allow for suction on the nipple. They aid eating by holding food in the mouth, creating an airtight seal that prevents liquids from escaping the oral cavity.1

Additionally, the lips are an integral part of the speech apparatus. They are involved with vowel rounding and the creation of bilabial “m,” “p,” “b,” and labio-dental “f” and “v” consonant sounds.1

Each person has a distinct pattern of grooves and sulci formed by the labial mucosa, similar to how fingerprints are unique to an individual.1

Variations of Normal and Pathology of the Lips

During an intraoral and extraoral exam, patients may present with lip anomalies. Below are examples of variations of normal and pathology.

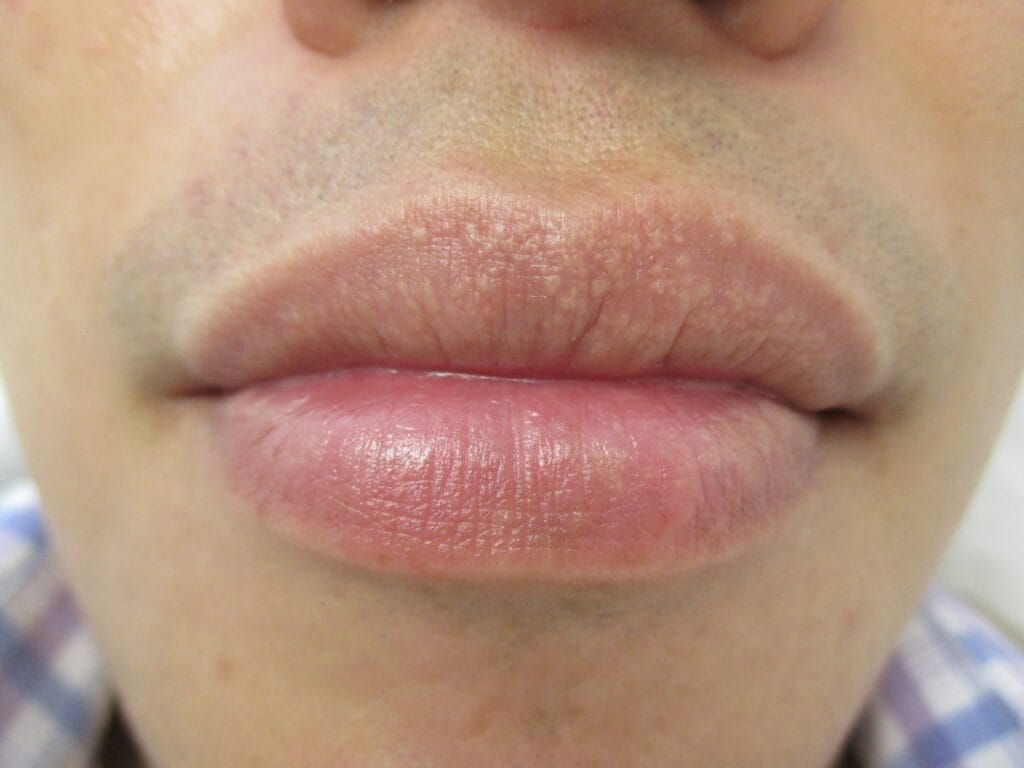

Fordyce Spots

Fordyce spots are normal findings presenting as small, slightly raised, smooth, yellow-white spots on the vermilion border of the lips or oral mucosa (see Image 1). They occur in approximately 85% of the population and are usually one to five millimeters in diameter.2

These spots are a variant of sebaceous glands containing neutral lipids similar to those found in skin sebaceous glands, but these are not associated with hair follicles. Fordyce spots usually become apparent during or after puberty.2

Fordyce spots are generally asymptomatic and harmless and do not require treatment.2 However, it has been suggested that higher numbers of Fordyce spots are associated with an elevated lipid profile (hyperlipidemia). Further studies are needed to confirm or refute this potential association.3

Courtesy of Leung, A.K.C., et al.3

(CC BY 4.0 DEED)

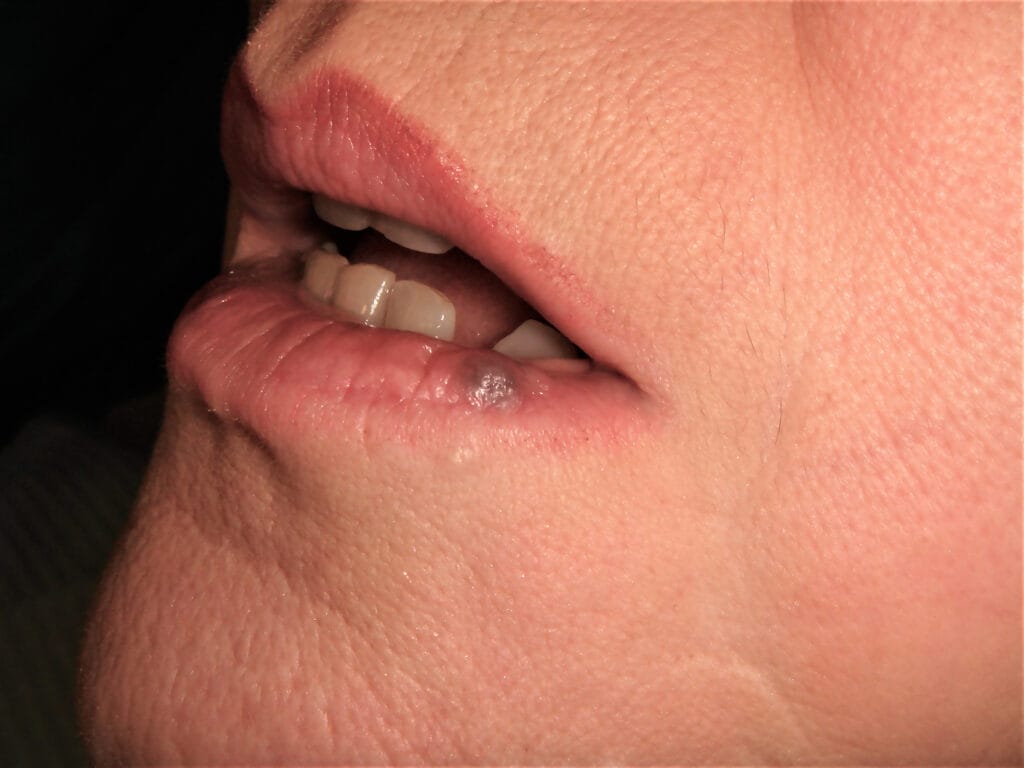

Caliber-Persistent Labial Artery

Caliber-persistent labial artery (CPLA) is a vascular abnormality of the lip caused by the fracture of the inferior alveolar artery to appropriately taper during its superficial course after exiting the mental foramen. CPLA presents as a palpable artery coursing two to three millimeters inferior to the vermilion border (see Image 2). CPLA has an incidence of only 3%, and 80% of cases involve the lower lip.1,4

This condition may be caused by trauma or lip biting. It occurs more frequently with aging, which suggests a degenerative process of the vascular wall may be involved.1

Excisional biopsy is not recommended due to the risk of profuse bleeding. Instead, a noninvasive diagnostic tool such as Doppler ultrasonography should be used. However, this condition is benign and does not require treatment.1,4

Courtesy of Llamas Carmona, J.A., et al.4 Original image has been cropped. (CC BY 4.0 DEED)

Venous Lakes

Venous lakes are benign, soft, and compressible papules that more frequently affect the lower lip in older adults. These papules can be flat or dome-shaped and may present as red, purple, or blue in color (see Image 3). Histopathologically, venous lakes show several dilated vascular spaces with erythrocytes and occasional thrombi lying on the irregularly arranged fibrous stroma.1,5

These papules are asymptomatic and do not require treatment. However, they may present a cosmetic concern and can be removed by surgical excision or diode laser therapy.1,5

Courtesy of Capodiferro, S., et al.6

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

Labial Melanotic Macules

Labial melanotic macules are benign, freckle-like lesions of focal hyperpigmentation of labial mucosa (see Image 4). These macules are caused by an increase in melanin deposition within the connective tissue of the lip without a change in the size or quantity of melanocytes.1

Labial melanotic macules may be difficult to differentiate from a venous lake. A venous lake, though, has a structureless pattern or globules with purple, blue, or red coloring, while labial melanotic macules are brown in coloration with parallel lines, dots, or circles.5

Labial melanotic macules account for 86.1% of oral lesions that involve melanin. They are benign and require no treatment but may be removed by excision, cryotherapy, or laser for cosmetic purposes.7

Courtesy of Duan, N., et al.8

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

Herpes Labialis

Herpes labialis is caused by infection of the lips with herpes simplex virus, most commonly HSV-1, although HSV-2 may occasionally be implicated. The main characteristic of the Herpesviridae family of viruses is that they go against replication within host cells without ever being completely eliminated, causing a latent infection by remaining dormant in the sensory ganglia of the trigeminal nerve.1,9

Risk factors for orolabial herpes include any activity that exposes a person to an infected person’s saliva, such as shared drinkware or utensils, cosmetics, and mouth-to-mouth contact.10 The incidence of HSV-1 is between 70% to 80% and is usually acquired in childhood.9

Symptoms of a primary orolabial infection occur between three days and one week after exposure. An initial infection has a more substantial presentation than reactivation, manifesting as fever, tender lymphadenopathy, localized pain, pharyngitis, gingivostomatitis, cheilitis, and perioral vesicles in young children. Patients then demonstrate painful, grouped vesicles on an erythematous base (see Image 5). These vesicles progress to pustules, erosions, and ulcerations.1,10

After two to six weeks, the lesions crust over, and symptoms resolve. Recurrent orolabial infections are milder than primary infections, presenting first as a 24-hour prodromal period of tingling, burning, and itching followed by a papulovesicular eruption on the vermilion border of the lips. These lesions crust over and resolve within approximately 10 days.1,10

Triggers for reactivation include ultraviolet (UV) light, menstruation, stress, trauma, and chemotherapeutic medications such as doxorubicin, prednisone, and vincristine.1,11 Current therapies for the treatment of orolabial herpes are pharmacological, topical, systemic, or instrumental (laser).9,10

Image courtesy Saleh, D., et al.10

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

Cheilitis

Cheilitis is an inflammation of the lips that could be acute or chronic and includes many types. The inflammation primarily arises in the vermilion border but may extend to the surrounding skin and, less commonly, to the oral mucosa. Several factors, including contact irritants, allergens, chronic sun exposure, nutritional deficiencies, and various cutaneous and systemic illnesses, may cause cheilitis. There is no definitive recommendation on diagnosing all types of cheilitis.12,13

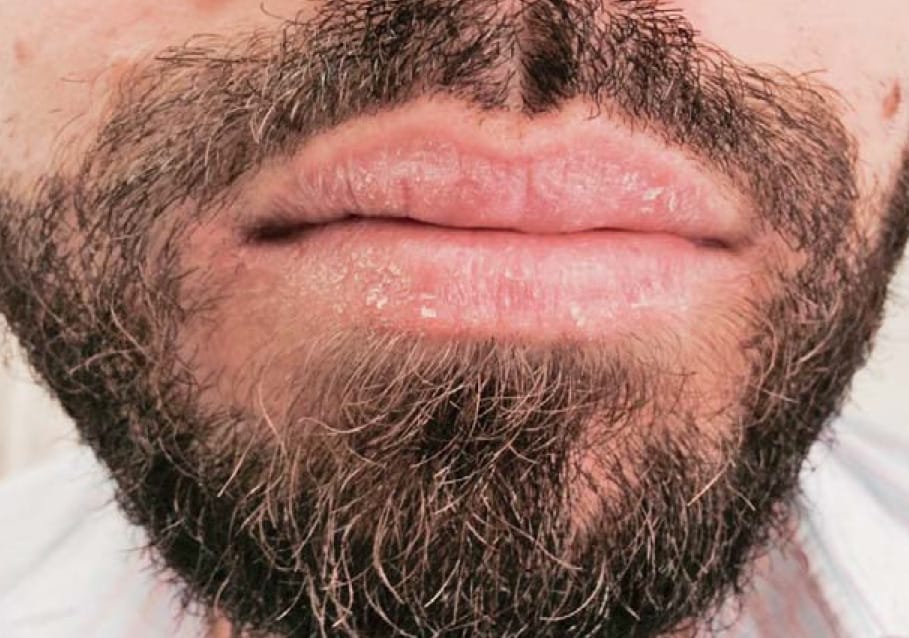

Cheilitis Simplex

Chieilitis simplex is the most common reversible subtype of cheilitis, presenting as cracked lips, fissures, or desquamation of the lips, usually the lower lip (see Image 6). Related factors include lip licking and cold, windy, and dry weather. Lip licking removes the thin, oily surface film that protects the lips from moisture loss that leads to lip cracking.13

The digestive enzymes of saliva can irritate the lips by extracting moisture and causing evaporation. Therapy involves advice on environmental conditions and the application of lip balms, petroleum jelly, emollients, topical corticosteroids, and ointments.13

Courtesy of Lugović-Mihić, L., et al.13

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

Allergic Contact/Eczematous Cheilitis

Allergic contact/eczematous cheilitis is a delayed type of hypersensitive reaction to allergens that come in contact with the lips and can cause lip inflammation. This subtype is very common and often caused by lipsticks, oral hygiene products, foods, ointment bases, fragrance preservatives, antioxidants, dyes, dental materials, musical instruments, or objects that are put in the mouth, such as pens, sewing needles, and nails.12

Allergic cheilitis manifests as dryness, scaling, erythema, or fissuring (see Image 7). It is treated with low to moderate-potency topical steroids or emollients.13

Courtesy of Lugović-Mihić, L., et al.13

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

Angular Cheilitis

Angular cheilitis typically manifests at the corners of the lips or mouth (see Image 8). Angular cheilitis is also known as perleche, cheilosis, angular stomatitis, or angulus infectiosus. The most common cause of angular cheilitis in adults is a fungal infection from Candida albicans and, less commonly, Staphylococcus aureus.12,13

Other related factors include nutritional deficiencies (i.e., B vitamins, iron, zinc) and ill-fitting dentures that cause drooling. Those with diabetes, celiac disease, and HIV are also at a higher risk of developing angular cheilitis. Salivary production is important as hypersalivation may increase risk with drooling, and hyposalivation promotes dryness, desquamation, and the allowance of C. albicans invasion.13

Therapies for angular cheilitis involve the elimination of predisposing factors, topical antimycotics, antiseptics, antibiotics, and topical corticosteroids.13

Courtesy of Bhutta, B.S., and Hafsi, W.12

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

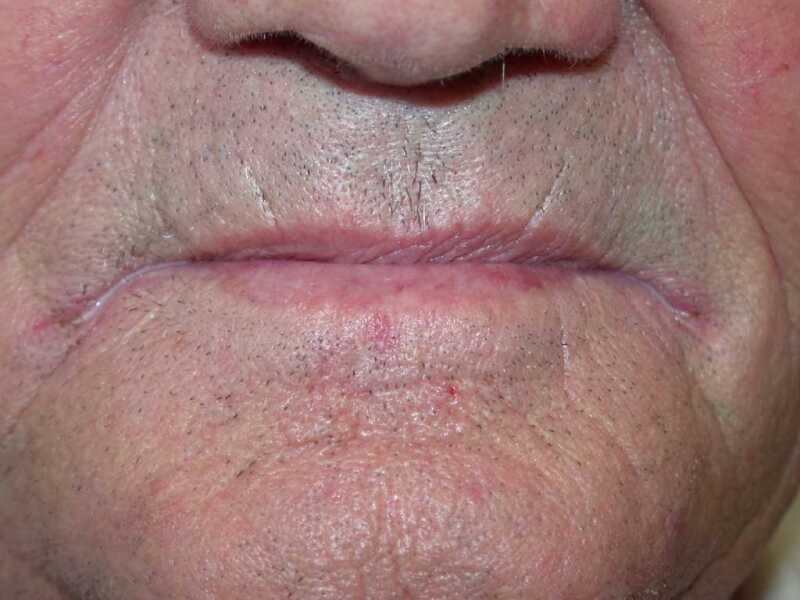

Actinic Cheilitis

The actinic cheilitis subtype is rare but not reversible and calls for biopsy and histology. Known as actinic keratosis or solar keratosis, this condition originates from the proliferation of atypical epidermal keratinocytes due to chronic sun exposure. It appears most commonly in the fourth to eighth decade of life in fair-skinned groups of outdoor employees such as sailors, agricultural, and construction workers.12,13

Actinic cheilitis clinically manifests as a painless thickening and whitish discoloration at the borders of the lips and skin (see Image 9). The vermilion border becomes less clear, and the lips may gradually become scaly and indurated. These lesions have a characteristic “sandpaper” feel to the touch.12,13

These lesions are considered premalignant conditions that occasionally progress to squamous cell carcinoma. A biopsy is recommended to rule out severe dysplasia or cancer. Therapy involves one or a combination of a low to moderate-potency topical corticosteroid, 5-fluorouracil, chemical peel cryotherapy, electrosurgery, vermilionectomy, immunosuppression, and surgery.13

Courtesy of Bhutta, B.S., et al.12

(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

Cancer

Cancers of the lip, tongue, cheek, floor of the mouth, and hard palate have been primarily classified under the group category of oral cancers. Among these cancers, the most undesignated and understudied type of cancer is lip carcinoma, even though lip cancer corresponds to 25% to 30% of all diagnosed oral cancers.14 In the United States alone, there are 40,000 cases of lip cancer a year.15

Risk factors include tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, excessive sun exposure, human papillomavirus, and weakened immune system. Fair-skinned men over the age of 40 years old are at high risk.15

Exposure to sunlight is one of the most commonly known causes of the development of lip cancer. Cells in the lip region are continuously exposed to various DNA-damaging agents from exogenous and endogenous sources. Flaws in DNA repair mechanisms involved in eliminating these damages may be linked to the origin of carcinogenesis.14 Basal cell carcinoma is a malignancy commonly associated with the upper lip. The risk of lymph node involvement or metastasis is low.1

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant neoplasm derived from the squamous epithelium and is the most common type of lip cancer. It affects the vermilion portion of the lip, which has the characteristic feature of being aggressively metastatic and having a high rate of recurrence even after treatment (see Figure 10). SCC can be difficult to differentiate from actinic cheilitis due to a tendency for both to progress slowly and asymptomatically.1

Early diagnosis is important to avoid metastasis. Surgical sectioning is standard for the treatment of lip cancers, followed by brachytherapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. Many factors, such as patient age, sex, comorbidities, and tobacco and alcohol use, can influence treatment strategies and their related outcomes. There is a relatively high long-term survival rate for malignancy of the lips. The recurrence rate is known to depend on the lesions beginning diameter, surgical margins, and invasion length.1,14

Courtesy of Coronation Dental Specialty Group

(CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED via Wikimedia Commons)

Dental Hygiene Evaluation

The lips play a critical role in facial expression, mastication, and phonation and should be carefully inspected at each dental visit. An extraoral exam includes a mouth mirror, explorer, periodontal probe, hand mirror, 2×2 gauze, air and water syringe, and personal protective equipment.16

Visually inspect the lips, including the commissures. Ask the patient to close and then ask them to smile. Use bi-digital palpation on the lower lip in a systematic manner from one corner of the mouth to the other, and then use the same technique for the upper lip.16

Notes should include normal, atypical, and abnormal findings with a highly detailed description of color, shape, size, and, if possible, extraoral photos of any lesions. Closely monitor any atypical or abnormal findings for changes, or refer the patient immediately for evaluation by an oral surgeon or dermatologist for more serious concerns such as suspected cancer.16

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on pure education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Piccinin, M.A., Zito, P.M. (2023, June 5). Anatomy, Head and Neck, Lips. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507900/

- Fordyce Spots. (2021, August 5). Primary Care Dermatology Society. https://www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/fordyce-spots-syn-fordyces-granules

- Leung, A.K.C., Barankin, B. Fordyce Spots. Clinical Case Reports and Reviews. 2015; 1(6): 121-122. https://www.oatext.com/Fordyce-Spots.php#Article

- Llamas Carmona, J.A., Rivera Mercado, Á., Lova Navarro, M., Gómez Moyano, E. Caliber-Persistent Labial Artery: Report of 3 Cases. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2022; 97(1): 99-101. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0365059621002567

- Lee, J.S., Mun, J. Dermoscopy of Venous Lake on the Lips: A Comparative Study with Labial Melanotic Macule. PLoS ONE. 2018; 13(10): e0206768. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0206768

- Capodiferro, S., Limongelli, L., Tempesta, A., at al. Diode Laser Treatment of Venous Lake of the Lip. Clinical Case Reports. 2018; 6(9): 1923-1924. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ccr3.1735

- What is a Melanotic Macule? (2023, January 9). Colgate. https://www.colgate.com/en-us/oral-health/adult-oral-care/what-is-a-melanotic-macule#

- Duan, N., Zhang, Y.H., Wang, W.M., Wang, X. Mystery Behind Labial and Oral Melanotic Macules: Clinical, Dermoscopic and Pathological Aspects of Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome. World J Clin Cases. 2018; 6(10): 322-334. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6163135/

- Crimi, S., Fiorillo, L., Bianchi, A., et al. Herpes Virus, Oral Clinical Signs and QoL: Systematic Review of Recent Data. Viruses. 2019; 11(5); 463. https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/11/5/463

- Saleh, D., Yarrarapu, S.N.S., Sharma, S. (2023, August 8). Herpes Simplex Type 1. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482197/

- Prasad, A., Remick, J., Zeichner, S.L. Activation of Human Herpesvirus Replication by Apoptosis. Journal of Virology. 2013; 87(19): 10641-10650. https://journals.asm.org/doi/full/10.1128/JVI.01178-13

- Bhutta, B.S., Hafsi, W. Cheilitis. (2023, August 17). StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470592/

- Lugović-Mihić, L., Pilipović, K., Crnarić, I., et al. Differential Diagnosis of Cheilitis – How to Classify Cheilitis? Acta Clinica Croatica, 2018; 57(2): 342-351. https://hrcak.srce.hr/en/file/304954

- Toprani, S.M., Mane, V.K. A Short Review on DNA Damage and Repair Effects in Lip Cancer. Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy. 2021; 14(4): 267-274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hemonc.2021.01.007

- Lip Cancer. (2024, October 7). Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21933-lip-cancer

- Darby, M.L., Walsh, M.M. (2009). Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice (3rd ed., pp. 219). Saunders.