Patients come to your dental office because they are looking to improve or maintain their health. Unfortunately, news stories too often emphasize the opposite effect. A patient becomes sick or even hospitalized, apparently because they visited a dental office. One recent report that made national headlines highlighted the tragic story of a seven-year-old girl, who had to have four teeth and part of her jaw bone removed as a result of infection (13).

She and 20 other children were infected with Mycobacterium abscessus after pulpotomy treatments, which was linked with the waterlines in her dentist office. This bacterium is especially difficult to treat with antibiotics, making the surgery and removal necessary.

Without a doubt, these outbreaks don’t happen often. At the same time, even a small chance of infection for your patients should lead your office to take action. Many of your patients will come in with a compromised immune system, especially children, and elderly individuals. Others may be vulnerable because they take medicine, or recently had an organ transplant. When that happens, even a simple infection can quickly become serious.

To protect your patients, you need to make sure that you keep the office as sterile as possible. That includes asking yourself whether the waterlines in your dental office are clean, and if you are taking proactive steps to ensure they can cause no harm to your patients.

What Makes Your Waterlines Clean?

The answer to this question is not a judgment call. Instead, a number of regulatory boards and commissions have put forth guidelines to ensure cleanliness. Put simply; you should be able to safely drink any water that comes through your waterlines. More specifically, here are some guidelines from various governing bodies:

- The American Dental Association Board of Trustees and Council of Scientific Affairs has advocated for clean waterlines since 1995 (1). In a statement that year, the ADA highlighted the importance that “no more than 200 colony-forming units (CFU) of aerobic mesophilic heterotrophic bacteria at any point in time in the unfiltered output of the dental unit.(1)”

- A 2003 guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) got more specific, recommending that “the number of bacteria in water used as a coolant/irrigant for nonsurgical dental procedures should be as low as reasonably achievable and, at a minimum, ≤500 CFU/mL.” The ADA has since updated its guidelines to reflect this recommendation (1), which is consistent with similar guidelines by the Environmental Protection Agency, the American Public Health Association, and the American Water Works Association (11).

What is lurking in your dental unit waterlines?

Understanding the need for clean waterlines becomes easier once you understand the dangers of neglecting this practice. The CDC has highlighted the fact that this is a common environment for the production and reproduction of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa (11). These, in turn, serve as a breeding ground of planktonic microorganisms that that can further contaminate the water (11). Organisms found in dental waterlines include:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can lead to blood infections and pneumonia. Even healthy patients, especially children, can suffer from ear and infections, as well as rashes as a result of exposure. Making matters worse, one in nine appearances of this bacterium are resistant to antibiotics (7).

- Legionella, while these bacteria are commonly found in nature, they typically don’t appear frequently enough to be harmful. That changes when it grows in waterlines, where its growth accelerates. It’s relatively resistant to chemicals and prefers warm water environments (5). When spread in your dental office, it can result in serious (and sometimes fatal) versions of pneumonia (6).

- Nontuberculous Mycobacterium, if your patients get infected by this species, they will need to take medication for at least 12 months. Worse, neglect or lack of medicinal treatment can lead to lung infections that eventually become chronic (2), (10).

- Staphylococcus aureus, you might think of it as harmless; almost one-third of the general population actually carry this bacterium in their nose. Especially patients with a weak immune system are not so lucky, especially if they already suffer (or have suffered) from diabetes, cancer, eczema, or lung In that case, it can cause serious conditions like sepsis and pneumonia. Staph bacteria are also increasingly immune against antibiotics, making treatment more difficult (4).

All of these examples have been found in dental waterlines that do not meet cleanliness standards (11), (12). Some of them are even immune to chemicals, making contamination more difficult to prevent.

Why are Clean Waterlines Difficult to Achieve for Dental Offices?

Dental offices tend to be more easily exposed to water contamination, largely because their waterlines differ to regular plumbing in both uses and set up (8). Water flows less frequently, which means that it stands in the line more often. Stagnant water, of course, can facilitate bacteria growth.

Comparing dental water use with that of an average family highlights these difference. A family of four uses about 200 to 300 gallons of water every day, which means that water flows through the pipes at up to 10 gallons every minute. A dental office, on the other hand, only tends to use up to 2 liters of waters per day, largely in the form of aerosol applications. That means only up to 50 milliliters actually flow through your pipes in a given minute (8).

Because of this lower use rate, dental pipes tend to be much smaller than their residential alternatives. Household plumbing uses standardized 1/2 in-wide water tubes, while dental offices use pipes that are eight times smaller at 1/16 inches in diameter (9). As a result, bacteria are left on their own to grow more easily within the pipes.

The Risks of Contamination Beyond the Patient

Naturally, and as highlighted the introduction, contaminated water lines carry significant risk for your patients. But that risk extends to physicians, as well. In fact, examinations showed that more than one-third of all dental staff had been exposed to the above-mentioned Legionella, compared to only 4 percent of the general population (14).

News stories also exist beyond patients. After a dentist passed away in California about two decades ago, water samples showed that Legionella bacteria persisted in much higher levels at his office than at home. No definitive conclusion was possible, but the likelihood that his death was connected to contamination at his dental unit is significant (3).

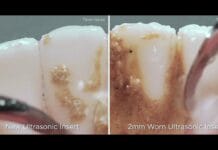

A similar story highlighted a serious eye infection by a dental hygienist in Washington after her eye was exposed to water from her ultrasonic scaler. Lack of waterline and supply tubing maintenance seems to have been the cause for pathogenic Serratia bacteria in her waterlines, which led to the infection (9).

To be clear, these are individual case studies that will not necessarily apply to you. Healthy individuals are unlikely to incur significant damages or diseases even from contaminated waterlines. The fact, that dental professionals are constantly exposed to these types of contamination undoubtedly presents a risk that requires an emphasis on cleanliness.

How to Keep Your Dental Waterlines Clean

As you might expect, regular maintenance is the key to success when avoiding potential and eliminating existing contamination. Choose the right treatment products, and follow the instructions on how to use them precisely.

Because of the short half-life of bacteria (they can double every twenty minutes in the right environment (9), your cleaning habits should include daily maintenance. As an example of the quick growth of bacteria, let’s say your waterline has one bacteria at 8 am, by noon there is now 4,096 bacteria, and by 5 pm there is now 134,217,728 bacteria present (9). Imagine what the bacterial count would be overnight when the water is absolutely stagnant or even over the weekend! Protocols can help in standardizing the operation, making sure that your water never remains stagnant for long. Daily updates and efforts are a must.

Of course, proper maintenance of any equipment connected to and using water is another important step. Here, follow the CDC guidelines:

Dental devices that are connected to the dental water system and that enter the patient’s mouth (handpieces, ultrasonic scalers, air/water syringes) should be operated to discharge water and air for a minimum of 20-30 seconds after each patient (11).

This step ensures that any patient fluid that may have entered the equipment or waterline can be flushed out. This step is more important than a past recommendation by the CDC, highlighting the need to flush waterlines at the beginning of each day (11).

Most dental offices already effectively maintain their waterlines on a daily and weekly basis. However, they often don’t “shock” their lines, which is a vital step to minimize bacteria growth before regular maintenance. Periodically, you should test your water either in your own office or externally through a lab, as recommended by the CDC (11).

As you prevent contamination, use a cleaning product to flush all tubing in the operatory – this can be one of the dirtiest areas in your water supply. A dental unit service firm can replace potentially problematic quick disconnects. The same technician can also help in maintaining and improving the tubing that connects to your handpiece, which can be fixed through a screw in the control block that stops any water from entering.

Finally, pay special attention to the areas where water needs to be warm for your patient. The warmer the water, the more easily bacteria can grow. Proper maintenance and minimized use are absolutely vital. All of these can turn into problems, even if your dental unit is not connected to city water. In fact, independent water systems can promote bacterial contamination (9).

What Products Can Help to Keep Your Waterlines Clean?

Just as you choose surface-area cleaning products based on their balance between efficacy and protecting the surfaces on which they’re used, the same should be true for the products you use to treat your waterlines. Harsh products with high acidic or basic components can damage your unit’s control block and lines.

Chemicals should be another consideration in your choice of product. Strike a balance between chemicals that are effective, but without harming humans or nature. That means staying away from bleach-based products, which might kill bacteria but also damage your equipment and emit chloroform (9). A simple test is to read the safety data sheet and make sure you’re comfortable using the product for yourself or your patients.

Summary

In most cases, even contaminated waterlines will not lead to serious infections or diseases. However, even continued exposure of less extreme bacteria can be harmful in the long run. Also, you don’t want to expose yourself, your staff, or your patients to any potential harm, even if the risk is low.

That’s what makes maintenance of your dental unit waterlines so important. The clinician-patient relationship involves a high level of trust, and much of it relates to keeping any individual who walks in the door healthy. Your patients trust you to follow the necessary protocol to improve, not harm their health. It makes sense to apply the same safety and disinfection standards you already use for your equipment and surfaces for the waterlines that supply water for your dental unit.

DON’T MISS: 5 Infection Control Mistakes You Might Not Realize You’re Making

Now Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

1) American Dental Association. (2016, Aug). Dental Unit Waterlines. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/dental-unit-waterlines

2) American Lung Association. (2016). Learn about Nontuberculous Mycobacteria. Retrievedfromhttp://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/nontuberculosismycobacteria/learn-about-ntm.html?referrer=https://www.google.com/

3) Atas, R.M., et. al. (1995, Jan). Legionella Contamination of Dental Unit Waters. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, Apr. 1995, p. 1208–1213. Retrieved fromhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC167375/pdf/611208.pdf

4) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011, Jan). Staphylococcus aureus in Healthcare Settings. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/staph.html

5) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, June). Legionella (Legionnaires’ Disease and Pontiac Fever). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/legionella/clinicians/diseasespecifics.html

6) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, July). Legionnaires’ Disease. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/legionella/downloads/fs-legionnaires.pdf

7) Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, May). Health-care Associated Infections :Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Healthcare Settings. Retrieved fromhttp://www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/pseudomonas.html

8) Chandler, J. (2002). Dental Waterlines: Understanding and Controlling Biofilms and Other Contaminants. Retrieved from https://www.hufriedy.com/products/index.php/mastercontrol/index/file/id/68

9) Dean Swift, B.Sc. B.Ed. FADM. If We Had Only Known… Reactions to Dental Waterline Contamination PDF and personal communication.

10) Ioachimescu, O.C., Tomford, J.W. (2010, Aug). Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disorders. Retrieved fromhttp://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/infectiousdisease/nontuberculous-mycobacterial-disorders/

11) Kohn, W.G., Collins, A.S., Cleveland, J.L., Harte, J.A., Eklunt, K.J., Malvitz, D.M. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings – 2003. MMWR 2003; 52 (Report No. 17). Retrieved fromhttp://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5217.pdf

12) O’Donnell, M.J., et. al. (2011, Oct). Management of Dental Unit Waterline Biofilms in the21st Century. Future Microbiol. 2011 Oct;6(10):1209-26. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.104. Retrievedfromhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22004039

13) Ross, E. (2016, Sept 30). Infection Outbreak Shines Light on Water Risks at Dentists Offices. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/healthshots/2016/09/30/495802487/infection-outbreak-shines-light-on-water-risks-at-dentists-offices

14) Szymanska, J. (2004). Risk of Exposure to Legionella in Dental Practice. Ann Agric EnvironMed 2004, 11, 9–12. Retrieved from http://www.aaem.pl/pdf/11009.pdf