Healthy teeth and gingiva impact our overall health and well-being. In a new study, researchers explored the use of ultraviolet-C (UV-C) light in fighting Streptococcus mutans, a bacterium associated with tooth decay.

Clinical Uses for Ultraviolet-C Light

The sun emits UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C irradiation. Ultraviolet light intensity is measured in milliwatts per square centimeter per second (mW/cm² * seconds) and exists in the electromagnetic spectrum between x-rays and visible light. Both UV-A and UV-B are linked to skin cancer, hence why doctors encourage sunscreen use. On the other hand, UV-C is mostly harmless to humans, but in microorganisms, it reduces their viability by preventing DNA replication. Due to this effect, UV-C light is germicidal. The earth’s ozone layer blocks almost all UV-C irradiation, but artificial sources like mercury vapor lamps can generate it.

Streptococcus mutans and Dental Caries

According to the CDC, tooth decay may lead to complications with eating, speaking, playing, and learning. Estimates show that more than half of adolescents, and around 90% of adults, have at least one cavity. Streptococcus mutans is one of the many microbes found in our complex oral environment and is considered to be a leading cariogenic, or cavity-causing, bacteria. It consumes sugar and starch that we eat, producing acid, hence causing enamel demineralization.

The Study

Previous studies show hope in using UV-C irradiation to fight cariogenic bacteria, but this is the first study to specifically look at Streptococcus mutans, hypothesizing that UV-C light may stop its growth. Researchers conducted two different experiments, looking at Streptococcus mutans in single layers and in colonies.

In experiment 1, researchers obtained a clinical isolate of S. mutans, made a bacterial culture, and transferred it to agar plates in single layers using the sterile-bead method. They exposed these samples to UV-C energies of 2.8, 3.5, 6.3, 7, 10.5, and 21 mWs/cm². They were then incubated, scanned, and counted by a specially-made computer program.

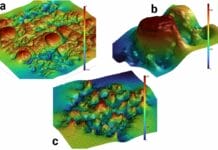

In experiment 2, researchers created bacterial colonies of S. mutans in order to mimic plaque. Four saliva samples were collected from a subject on plastic strips and then cultured. Half of each strip was exposed to UV-C energies of 210, 420, 630, and 1050 mWs/cm², while the other half was covered with UV-protective glass. Then, the irradiated areas were scraped, prepared for analysis, transferred to agar plates, and analyzed under a microscope.

Results

In the first experiment, 11 mWs/cm² killed 95% of the single-layer bacteria, and 21 mWs/cm² killed them all. In the second experiment, UV-C irradiation significantly reduced the number of bacteria but did not fully kill it; at 1050 mWs/cm² it exhibited a bacteriostatic effect with a 6% survival rate. These findings are in accord with similar studies on oral bacteria and UV-C light, but this is the first study to explore the effects of UV-C irradiation on S. mutans.

Single layers of S. mutans were more sensitive to UV-C light in comparison to the biofilm. One possible explanation for this phenomenon may be due to the complex array of microbes in the biofilm, thus acting like a shield preventing UV-C light from reaching layers of bacteria underneath. As a result, some bacteria survived.

This study shows promise in reducing oral cariogenic bacteria in plaque with UV-C light, but as with most in vitro studies, in vivo outcomes may differ. A limitation of this study may be the 24-watt UV lamp, and further studies should look at the effects of higher UV-C energies on Streptococcus mutans.