Historically, the United States has a low rate of tuberculosis (TB). However, there has been an outbreak of TB cases in Kansas. The outbreak has led to 67 reported active cases and two deaths as of January 31, 2025, making it one of the largest United States outbreaks of TB in the past 30 to 40 years.1

It is important to note that the cases in the ongoing outbreak in Kansas did not all appear in January 2025. The outbreak has been ongoing for at least a year, maybe longer. TB outbreaks often last for extended periods due to the length of time required for appropriate treatment.1

Additionally, symptom onset can be delayed or mild. Consequently, those infected may not seek medical care. This delayed diagnosis due to delayed or mild symptoms can increase the number of people exposed, contributing to outbreaks of TB.1,2

Though TB is curable and preventable, it causes higher mortality globally than any other infectious disease. This is primarily due to weak public health infrastructure and drug resistance. An estimated 10.8 million people were infected with TB, and 1.23 million people died from TB worldwide in 2023.1,2

With the ongoing outbreak, it is worthwhile for dental hygienists to refresh their knowledge of TB, including managing transmission risks, infection control protocols, and orofacial manifestations of TB. Knowing TB signs and symptoms can aid in early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, and proper infection control practices can prevent and reduce the spread of TB to dental professionals and patients.

Tuberculosis Etiology

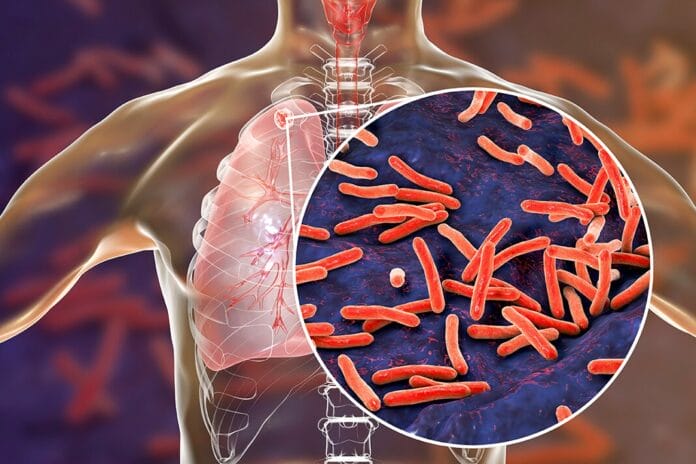

TB is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It is spread through the air and can linger in the air for several hours. As a result, close contact is not necessary for TB to spread. It is one of the few genuinely airborne infectious diseases.1

The bacterium that causes TB was first discovered in 1882 by Dr. Robert Koch. However, M. tuberculosis has been infecting humans for much longer. Archeological evidence shows human infection dating back 9,000 years, with written records of the disease found in India dating back 3,300 years ago. Yet, it is estimated that M. tuberculosis has been around for three million years.3

Tuberculosis Surveillance

Surveillance in the United States began in 1889 when cases of TB began to be reported by doctors in New York. The first report was published in 1893.3

From 1953 onward, cases of TB in the entire United States have been reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System (NTSS). The CDC began publishing an annual report on TB cases in 1993.3

To bring awareness, the global health community established March 24th as World TB Day in 1982.3

Tuberculosis Testing

Testing for TB can be done using a skin test or a blood test. Skin tests are performed by putting a small amount of tuberculin, an extract of the TB bacilli, under the skin and measuring the body’s reaction. TB skin testing has been utilized since the early 1900s and is still used today.3

TB blood tests are a more recent advancement. TB blood tests measure how your immune response reacts when a small amount of blood is mixed with TB proteins.3

If either the TB skin test or TB blood test is positive, further diagnostic testing is used to confirm the diagnosis and determine if the TB is latent or active.3

Tuberculosis Treatment

Treatment varies depending on the diagnosis. Inactive or latent TB is treated with multiple medications. The treatment protocol can take three, four, six, or nine months. The combination of the following medications is the recommended treatment protocol for latent TB:3

- Isoniazid

- Rifampin

- Rifapentine

Similarly, active TB can be treated by several different treatment protocols. The treatment protocols consist of multiple medications that must be taken for four, six, or nine months. Medications used for active TB treatment protocols include:3

- Ethambutol

- Isoniazid

- Moxifloxacin

- Rifampin

- Rifapentine

- Pyrazinamide

Tuberculosis Drug Resistance

Drug-resistant TB is a form of infection caused by bacteria resistant to at least one of the most effective TB medications used in treatment protocols. It occurs via two different mechanisms: primary drug resistance and secondary drug resistance.4

Primary drug resistance simply refers to person-to-person transmission of drug-resistant TB bacteria.4

Secondary drug resistance develops during TB treatment. This can occur through multiple mechanisms:4

- When a patient is not treated with the appropriate treatment regimen

- When a patient deviates from the prescribed treatment regimen, such as taking medication incorrectly, irregularly, or not completing the regimen

- When a patient’s body does not absorb the drug as expected

- When drug interactions cause low serum levels of the drug being used to treat TB disease

Tuberculosis Prevention through Vaccination

The bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine is available for the prevention of TB. The BCG vaccine was developed in 1921 and is primarily given to infants and children in countries with endemic TB infections.3 However, the vaccine is not utilized in the United States due to the generally low case rates of TB infection and disease, the variable effectiveness against adult pulmonary TB, and the potential to cause a false positive on a skin test.3,5

The vaccine’s protection does weaken over time.3 Once vaccinated, the best way to test for potential infection is through a blood test rather than a skin test because of the risk of a false positive.3,5

Managing Tuberculosis Transmission Risks in Dental Settings

In the United States, TB infection rates generally remain low, with the most susceptible individuals being those that are immune compromised, infants and children less than four years old. Additional environmental factors can increase the risk of infection, including smoking, indoor air pollution, and poor nutrition.3,6

The risk of acquiring TB in a health care setting depends on multiple factors. Historically, TB infections acquired in a health care setting have been attributed to treating patients with active TB during aerosol-generating or aerosol-producing procedures. Numerous studies show a decline in health care-associated transmissions with rigorous implementation of infection control measures.6

Ideally, patients with active TB should not be treated in a dental setting. However, there are risks of patients presenting who have not been diagnosed during outbreaks. It is important to note that individuals with latent TB are not infectious and can be treated in a dental setting using standard precautions without concern.6,7

However, an estimated 10% of people with latent TB can develop active disease. Therefore, it is imperative they receive the appropriate treatment for their infection to prevent the risk of developing active disease. Standard precautions are insufficient to treat patients with active TB in dental settings.6,7

TB screening questions should be included on medical history forms to help manage the risk of transmission. When reviewing medical history, dental professionals should routinely document whether patients have symptoms or signs of TB disease.6,7

Respiratory TB symptoms to inquire about when screening include:6,7

- Coughing for more than three weeks

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Night sweats

- Bloody sputum

- Hoarseness

- Chest pains

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Presence of persistent lesions of the oral mucosa that are non-responsive to therapy

If active TB is suspected, the patient should be removed from areas with other patients or staff and be instructed to wear a mask. The urgency of their dental treatment should be assessed, and they should be promptly referred to an appropriate medical setting to evaluate possible infectiousness. Nonurgent and elective dental treatment should be postponed until a physician has declared the patient noninfectious.6,7

Infection Control in Dental Settings

All dental settings should follow TB infection control measures even in the absence of an outbreak. However, it is worth brushing up on the guidelines when there is an outbreak.6,7

TB infection control is based on a three-level hierarchy of controls:6,7

- Administrative controls

- Environmental controls

- Respiratory protection controls

Administrative Controls

Administrative controls are the first and most important controls to implement in TB infection control. Administrative controls are meant to reduce the likelihood of an exposure. This type of control is based on changes in work procedures.6,7

Administrative controls for TB infection control include:6,7

- Assigning a team member to be responsible for TB infection control.

- Conducting an annual TB risk assessment.

- Develop and institute a written TB infection control plan, including guidance for immediately identifying and isolating suspected active TB patients.

- Ensure proper cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization of potentially contaminated equipment and surfaces.

- Ensure the disinfectant being used is hospital-grade with a tuberculocidal claim. You can find a list of EPA-registered antimicrobial products effective against Mycobacterium tuberculosis here.8

- Train and educate dental health care workers on signs, symptoms, prevention, and transmission.

- When hiring dental health care workers, screen for latent TB and TB disease.

- Use appropriate signage for respiratory and cough etiquette.

- Coordinate efforts with local and state health departments.

- Postpone nonurgent dental treatment for patients with suspected active TB disease.

Environmental Controls

The second level on the hierarchy of TB infection control is environmental controls. Environmental controls are used to control and prevent the spread of TB in ambient air.6,7

Environmental controls for TB infection control include:6,7

- An airborne infection isolation room should be used for urgent dental treatment for patients with suspected or confirmed active TB.

- High-efficiency particulate air filters or ultraviolet germicidal irradiation should be used in settings with high volumes of patients with suspected or confirmed TB.

Respiratory Protection Controls

The first two control measures significantly reduce the number and areas in which one can be exposed to TB. However, these measures do not eliminate the risk entirely. Therefore, the third level of controls is meant to further reduce the risk of exposure to infectious droplets in the air.6,7

Recommended respiratory control measures for TB infection control in a dental setting include:6,7

- Use respiratory precautions – at least a disposable N95 particulate filtering facepiece respirator – for dental professionals providing urgent dental treatment to patients with suspected or confirmed TB.

- Instruct patients with TB to cover their mouth when coughing and to wear a surgical mask.

Orofacial Manifestations of Tuberculosis

Though TB primarily affects the lungs, it can also affect other organs and systems, including the oral cavity. Orofacial manifestations can affect sites such as the tongue, gingiva, palate, lips, buccal mucosa, and the floor of the mouth.9,10

TB is often overlooked in the differential diagnosis of oral lesions, as they are relatively uncommon and only occur in about 0.5% to 5% of all TB infections.13 Even so, recognizing and identifying oral TB lesions could ultimately assist in a timely diagnosis and treatment, leading to reduced morbidity and mortality.9,11

Oral TB lesions can be either primary or secondary. Primary lesions occur when TB bacilli enter the oral mucosa without prior TB infection.11 They are rare and typically affect younger patients, often accompanied by enlarged cervical lymph nodes.9-11 Secondary oral TB lesions usually occur secondary to pulmonary TB.11 While observed in all age groups, occurrence is more frequently seen in middle-aged and older adults.9-11

The gingiva is the most commonly affected site for primary oral TB lesions. Gingival presentation is a diffuse, hyperemic (increased blood flow), nodular, or papillary proliferation of the tissue. It usually presents as a single painless ulcer that progressively extends from the gingival margin to the vestibule. In some cases, there may be multiple lesions, and the lesions can be painful.9

Secondary oral TB lesions present as an irregular, superficial or deep, painful ulcer that slowly increases in size. It is most often found in areas of trauma and may be mistaken as a traumatic ulcer or suspected squamous cell carcinoma. The tongue is the most commonly affected site.9-11 Less commonly, secondary oral TB can present as an inflamed, granular, modular, or fissured lesion with no clinical signs of ulceration.9

The bone of the maxilla and mandible can also be involved in secondary oral TB. In some cases, the microorganisms can enter the periapical tissue through a cavitated carious lesion via the pulp chamber, causing a tuberculous periapical granuloma or tuberculoma.9

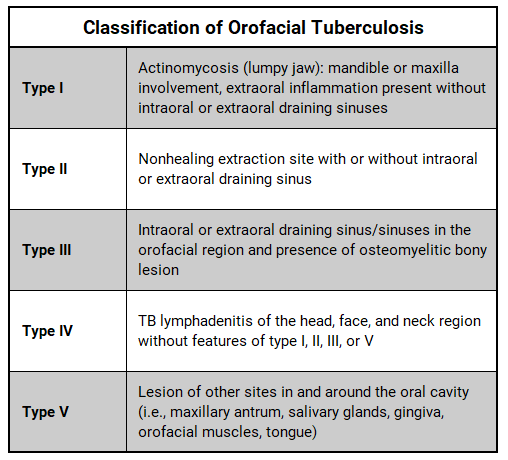

Orofacial TB lesions can be classified based on the affected site and presentation of the lesion.10

Oral TB lesions are difficult to diagnose and often misdiagnosed as their clinical presentation is nonspecific. Differential diagnoses include aphthous ulcers, traumatic ulcers, syphilitic ulcers, and malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma and lymphoma.9,11

Suspicious lesions should be further evaluated through diagnostics such as excisional biopsy with histopathological evaluation, AFB smear microscopy, AFB culture, and bacterial and fungal culture. TB testing and chest radiographs should be done to rule out systemic TB.9

Treatment for oral TB lesions is the same as treatment for systemic TB.9

In Closing

TB is rare in the United States, but the incidence has been steadily increasing.12,13 Rates have increased in the United States for the past three consecutive years. In 2023, 9,633 TB cases were reported, an increase of 16% from the previous year.13 Eight states and Washington DC reported higher rates than the national average in 2023. Case counts increased among all age groups and in both individuals born in and outside the United States.12,13

With the consistently increased rates of TB and the current outbreak in Kansas, it is worthwhile for dental professionals and dental offices to brush up on their knowledge and infection control protocols. Knowing TB signs and symptoms can aid in early diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Proper infection control practices can prevent and reduce the spread of TB to dental professionals and patients. Ensuring infection control practices align with current guidelines will provide a safer work environment while protecting patients from exposure to infectious diseases.

Doing our part in dentistry to end the current outbreak and reduce the incidence and prevalence of TB in the United States will ease the financial burden and improve overall health for the community at large.

Before you leave, check out the Today’s RDH self-study CE courses. All courses are peer-reviewed and non-sponsored to focus solely on high-quality education. Click here now.

Listen to the Today’s RDH Dental Hygiene Podcast Below:

References

- Rosen, A. (2025, February 6). What the Tuberculosis Outbreak in Kansas Means for Public Health. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2025/tuberculosis-in-kansas-the-larger-picture

- Tuberculosis. (2024, October 29). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

- History of World TB Day. (2024, December 5). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/world-tb-day/history/index.html

- Clinical Overview of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Disease. (2025, January 6). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/hcp/clinical-overview/drug-resistant-tuberculosis-disease.html

- Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) Vaccine for Tuberculosis. (2025, January 31). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/hcp/vaccines/index.html

- Jensen, P.A., Lambert, L.A., Iademarco, M.F., et al. Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Health-Care Settings, 2005. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2005; 54(RR17): 1-141. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5417a1.htm?s_cid=rr5417a1_e

- Tuberculosis. (2023, September 6). American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/tuberculosis-overview-and-dental-treatment-conside

- EPA’s Registered Antimicrobial Products Effective Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) [List B]. (2025, February 3). United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/epas-registered-antimicrobial-products-effective-against-mycobacterium

- Sharma, S., Bajpai, J., Pathak, P.K., et al. Oral Tuberculosis – Current Concepts. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019; 8(4): 1308-1312. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6510082/

- Azizah, A.N., Wahyu, N.I., Rahmadhani, A., et al. Oral Findings in Cadaver with Tuberculosis: A Case Report. e-GiGi. 2025; 13(1): 105-109. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381031640_Oral_Clinical_Findings_in_Cadaver_with_Tuberculosis_A_Case_Report

- Sriram, S., Hasan, S., Saeed, S., et al. Primary Tuberculosis of Buccal and Labial Mucosa: Literature Review and a Rare Case Report of a Public Health Menace. Case Rep Dent. 2023; 2023: 6543595. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10569891/

- Williams, P.M., Pratt, R.H., Walker, W.L., et al. Tuberculosis – United States, 2023. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2024; 73(12): 265-270. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7312a4.htm

- TB Notes Issue 3, 2024. (2025, January 13). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/connect/tb-notes-2024-3.html